A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar

Mixing a cocktail of philosophy, theology, and spirituality.

We're a pastor and a philosopher who have discovered that sometimes pastors need philosophy, and sometimes philosophers need pastors. We tackle topics and interview guests that straddle the divide between our interests.

Who we are:

Randy Knie (Co-Host) - Randy is the founding and Lead Pastor of Brew City Church in Milwaukee, WI. Randy loves his family, the Church, cooking, and the sound of his own voice. He drinks boring pilsners.

Kyle Whitaker (Co-Host) - Kyle is a philosophy PhD and an expert in disagreement and philosophy of religion. Kyle loves his wife, sarcasm, kindness, and making fun of pop psychology. He drinks childish slushy beers.

Elliot Lund (Producer) - Elliot is a recovering fundamentalist. His favorite people are his wife and three boys, and his favorite things are computers and hamburgers. Elliot loves mixing with a variety of ingredients, including rye, compression, EQ, and bitters.

A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar

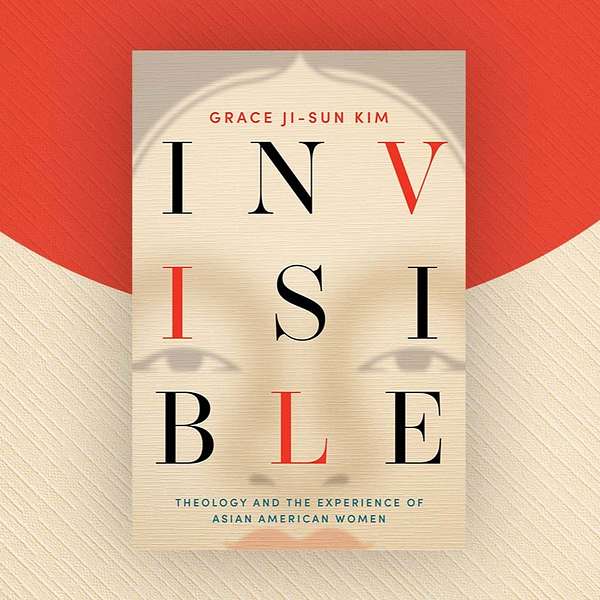

Theology from the Margins: An Interview w/ Dr. Grace Ji-Sun Kim

How do you process your identity and theology if you feel invisible as a person? What if your story, history, and experience are largely rejected and excluded from the culture you're a part of? How does that shape the way you see God and the world?

Dr. Grace Ji-Sun Kim is a Korean-American theologian who works in liberation and feminist theology and wrote the book Invisible asking those questions from her perspective as an Asian American woman. In this conversation, we talk about identity, whiteness, white supremacy, and how the Holy Spirit and the Asian concept of chi might be interwoven.

The bourbon we taste in this episode is a 1980 I.W. Harper. But don't go looking for it, because it's, you know, 43 years old. To skip the tasting, go to 7:19. You can find the transcript for this episode here.

Production note: Logic corrupted our files (thanks Apple), so we had to use Zoom audio this time. Apologies.

PS: Kyle was dealing with some family stuff and unfortunately couldn't make it for this interview. He'll be back next episode.

=====

Want to support us?

The best way is to subscribe to our Patreon. Annual memberships are available for a 10% discount.

If you'd rather make a one-time donation, you can contribute through our PayPal.

Other important info:

- Rate & review us on Apple & Spotify

- Follow us on social media at @PPWBPodcast

- Watch & comment on YouTube

- Email us at pastorandphilosopher@gmail.com

Cheers!

NOTE: This transcript was auto-generated by an artificial intelligence and has not been reviewed by a human. Please forgive and disregard any inaccuracies, misattributions, or misspellings.

Randy 00:06

I'm Randy, the pastor half of the podcast, and my friend Kyle is a philosopher. This podcast hosts conversations at the intersection of philosophy, theology, and spirituality.

Kyle 00:15

We also invite experts to join us, making public space that we've often enjoyed off-air around the proverbial table with a good drink in the back corner of a dark pub.

Randy 00:24

Thanks for joining us, and welcome to A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar. On this podcast, we do something a little bit unique. We taste whiskies usually, we taste an alcoholic beverage, because we love how that sets the table for great conversations. So Kyle, we've got something special here tonight. What's happening?

Kyle 00:48

Yeah, we do. So if you have been listening to the show, for a while, you might have heard a bonus episode that we did with our friends who run a YouTube channel called power of bourbon. And Tim, who is one of the hosts of that channel, and also one of our Patreon supporters, has been a good friend ever since and extremely graciously sent us a whole box of whiskey that we are so excited to taste. And so what we have done is we have so much of it. And we want to do all of it justice. And so we're going to do a series of tastings from this batch of things with Tim that he sent us. And so you're gonna hear different of these in various episodes for a little while. Yeah, and we're gonna taste them all blonde, so we don't know what it is going going into it. And so if you're wondering why Tim is showing up on the show a lot in the next few episodes. That's why

Randy 01:34

Yeah, that means you finally get to hear somebody who knows what they're talking Exactly, yes. Yeah,

Kyle 01:38

we're totally making it up. But Tim actually knows, Tim, welcome

Randy 01:40

to the show.

Tim 01:41

Thank you so much. I don't know how much it now but I know enough. We'll go with that. Yeah,

Kyle 01:45

there's a scene in parks and rec where Ron Swanson walks into, like a Home Depot or something. And somebody's like, just a hardware store and somebody comes up and asks him if he needs help. And he's like, I know more than you just keeps walking. That's you and I look.

Tim 02:03

There's a whole bunch of names about that with all of us. Perfect, guys.

Randy 02:05

All right, well, let's, let's do this.

Kyle 02:10

Yeah, I'm getting a lot of cherry on the nose to

Randy 02:13

dark matcha caramel color. It is. Yeah. It smells deep. Rich, but it's got some sweetness to it in the nose at least.

Tim 02:23

Mm hmm. Yep. Yeah, get out like old library smell to it and go. Corn.

Kyle 02:30

I'm gonna guess it's a medium to high proof just based on the nose. But we'll see. Oh, that's special. That's unusual.

Randy 02:46

It's got like, the front of my palate gets nailed with sweetness right away. And then it rounds out to the back and edges of my palate with the okayness with a smoke with some dark fruits. But that's complex. There's a lot going on in this in this bourbon. I'm assuming it's a bourbon. I don't know. 30? Maybe not. It doesn't taste like a right to me. So I'm gonna say bourbon.

Kyle 03:08

I think it's definitely bourbon. Yeah.

Randy 03:11

I don't know. This is real proof.

Kyle 03:13

I take back what I said about the proof. It was not as strong as I expected.

Tim 03:18

Yeah, so this bottle, the reason I chose it is it's special. And when you try it, you get that special miss in the in the tasting.

Kyle 03:28

So it's hard to put a word on what it is that makes it different. I mean, it's

Elliot 03:32

yeah, I'm glad that you're struggling. Maybe I just haven't had enough nice stuff to be able to identify. It's just so complex.

Randy 03:39

It it hits me at first, this is gonna sound so sacrilege to him. So I'm sorry for saying this. But I've got a friend who makes whiskey, and he makes really good whiskey. But it tastes at first it hits me with a little new Mickey, just sweetness of it. Because I mean, this is kind of raw, almost. But then it fills in with the complexity and you know, you're not tricking something that's new. If that makes sense. Yeah.

Kyle 04:02

I think there's a fair amount of age on it just because of how strong the wood is. It's almost like a tree bark. Yeah, yeah, level, but not in a bad way. And a little bit of char.

Tim 04:12

It's one of those that fills your whole mouth. It's not going to just go straight down the center or anything like that. It gets all the way into the jaw line and just really just hangs on and gives you guys

Elliot 04:23

it'll feel tingling.

Randy 04:24

Yeah, it gives you the tingly cheek. Yeah, for sure. All right, can you tell us

Tim 04:28

so this is IW Harper from 1980. Whoa, so that is when it was bottled. So this is what we call a dusty. So for my birthday, I got to go to a vintage liquor store and get some stuff. So this was distilled in the 70s bottled in the 80s. And it is just a regular IW Harper bottled and bought No,

Randy 04:54

that's incredible. So when it's in the bottle, it's been in the bottle for 40 years or something like that, too. It's done with all the changing and like it's done with the flavor, it doesn't do anything to sit in the bottle for 40 years does it?

Tim 05:07

As long as you keep it out of the sunlight and around 75 ish degrees, you know, plus or minus a couple, it won't change at all. And that also depends on like a good seal, so that it doesn't oxidize or anything like that. So when I was there, like we checked the seal and everything like that to make sure all that stuff was good.

Elliot 05:29

So none of the none of the kind of oddness of the flavor profile, you think comes from the fact that it's a dusty, as you said, like that's got to play into it somewhat. Right? Yeah. So

Tim 05:39

that little like when you said, it's got a little funk or something that you haven't tasted before, that's kind of a dusty note that you give. And also, we've changed like, with the types of corn, we've used distillation method, everything like that the environment changed, and that affects bourbon in so many ways, or well, so there's a lot of people and purists that are like everything before this time is way better than everything.

Elliot 06:04

Last time. This is what it tasted like before global warming. I love it.

Kyle 06:09

So how old was it when it was bottled?

Tim 06:12

So it's bottled and bond? So at least four years. Okay, but no age statement?

Kyle 06:15

Was it common to have eight statements back then?

Tim 06:19

No. I mean, you had the like, you know, straight which is over two years bottled and bond, which was four, but that was the original reason they did bottled and bond back in the day is because you had rectifiers and people like that, that what they would do is they would put additives in it. And so the reason bottled bottom came around was to protect it. So you knew this was authentic, pure bourbon that was not tainted in any way. Yeah.

Kyle 06:44

So when you had said to us before some of these things I sent you I'll never see again. I'm understanding why.

Randy 06:51

Tasting gets you know, into it turns into an episode. Tim, can you tell us one more time what we're drinking?

Tim 06:58

We're drinking IW Harper bottled and bond from the 1980s. Cheers.

Elliot 07:03

Thanks for sharing that.

Randy 07:20

Dr. Grace, Jason Kim, thank you so much for joining us Anna, pastor and a philosopher walk into a bar. Oh,

Grace 07:25

thank you so much for the invitation. I'm so excited to speak with you tonight. So thank you so much.

Randy 07:31

Absolutely. Dr. Kim, when we were off air, you just said you broke your knee in Israel Palestine, two days before the fighting broke out. How are you? Oh,

Grace 07:40

I am still in a lot of pain. I've actually hurt the same knee that I hurt or 15 years ago. But that time it wasn't broken. It was ripped meniscus, but had surgery on it. And then this time around, I was there and I saw on Apollo rocks inside a hotel. So still in a lot of pain, but grateful to be home. Came home two days before the airstrikes. So it's wonderful to be home. Yeah.

Randy 08:08

When I reached out to you, you have a number of books. How many books have you written? Dr. Kim?

Grace 08:13

Oh, I think 22 now.

Randy 08:18

No. And you wanted to you wanted to talk about your book invisible from 2021. Now, usually, we you know, in our interviews, we gear our conversations around a book, it's really convenient for quality interview. In this book and visible, it's about the most autobiographical book and the most personal book that we read on the podcast, I would say it's extremely personal, goes back into your roots, your ancestors, your culture in some profound ways in some really deeply personal ways. So usually I start out by asking Where did this book come from? But can you just tell us about yourself a little bit, your background? And yes, where this book came from Dr.

Grace 08:57

Kim, you know, I was born in Korea, and then our family emigrated in 1975 to Canada. So I write some stuff about growing up in Canada in the book. And we emigrated. Well, then myself and my own nuclear family, we moved to the US in 2004, to begin teaching here in the US, so my life is kind of separated into three parts. And as an immigrant child, I've experienced so much racism, and I think the common experience for many Asian Americans is this notion of being invisible. So I thought for a long time, I've kind of wanted to write this book. And the timing was right, and I just kind of wrote it, but I didn't realize how autobiographical it was until I was at the copy editing stage. And after I had submitted my manuscript to the publisher, I got really ill. So I was Hospital. realized. And then I didn't look at it for months, when the copy editing came, I realized I included all these personal stories. And I was a little bit in shock because I had forgotten they put the wallet. And I, I was debating Should I start deleting some of them and I realized if I start deleting, I'm gonna start deleting all the stories, which will mean that there'll be nothing left of the book. And for me as an Asian American theologian and as a feminist theologian, we do so much of our theology from our own experiences. So at the end of the day, I accepted and I kept all the stories, and they're all in the book. So for listeners, if you're curious about war details about my life, you can go and read this book. It's quite interesting when you said this was the most autobiographical book that you had on your podcast. My next book, or my next next book that's coming out is called when God became white. And I felt I put so much of my other stories in there I guess I have a ton of stories about my life. But I put a lot of my other personal stories in there are two

Randy 11:13

Korean one God became white one can we expect that

Grace 11:17

that'll be coming out in on May 7 2024. That's worth InterVarsity press, and it will line up with AAPI Heritage Month. So exciting that we could celebrate API's here in America. And it'd be a few days after my birthday. So it's gonna be exciting. May 2020. For each

Randy 11:40

well, can we book you right away for me in to interview about how God became with this incredible. So this book that we're talking about today is invisible urology and the experience of Asian American woman. Early on in the book, grace you, you paint this picture of Asian American woman being doubly marginalized, both out in the world in north or north america, whether in Canada or in America, and at home, can you tell our listeners about their reality and bring us into that world of being double W marginalized as an Asian American woman,

Grace 12:10

so many of us aren't just Asian Americans as a whole, we feel, you know, the concept of being invisible is one, another part of our identity is being marginalized. So we are never going to be part of the white dominant society or culture, because we are just visibly we look different. You and I, you're white, and Asian. So our features are different. If our kids never intermarry, you know we're going to have this visible identity. So in many ways we have become marginalized in society. We are the foreigner, we are the subordinated the oppressed kind of group. So our identity as marginalized people, is really central to our identity, as much as our experience of being invisible. So when you add in the layer of being an Asian American woman, within the Asian culture with the Asian North American culture, it is still very patriarchal. With Confucianism, just as a whole, many parts of Asia are very patriarchal. So as an Asian American woman, when we come back into our homes, you know, when I was growing up, it was very clear who the head of the household was, my father told us many times that he's the head of the household, and we all had to listen to Him and obey Him. So in that way, many Asian American women are doubly marginalized, once in society and then once within the household, or within the Asian American culture itself. Whether you go to church or in the Asian American community, it's very clear that it's still very patriarchal, and that women are subordinate to men.

Randy 14:08

In ways I want to bring out as many stories from the book as possible listeners, you should read this book. This is one of those books that I think is a must read. It's really really important and opened my eyes to a whole world that I had no idea existed to be honest with you. I feel terrible saying that, honestly, Dr. Kim, but it's, it's a reality. One of those little snapshots is when you talked about your what you called your Tiger uncle, and how he basically just watched him boss around your mom, even though she was a grown. I want to say grown a woman. But tell us about that. That Tiger uncle and just how that kind of is a microcosm of the patriarchy within whether it's Asian American families or

Grace 14:45

Yeah. Well, thank you so much for saying all those nice things about my book. I'm really excited about the book and I hope more and more people will read it because there's not that much interest in Asian American can literature or people as a whole. So I'm just thrilled when people want to read it and the readers will get a sense of, or they'll learn a lot about Asian Americans and Asian American woman, but I've always written it, so that it'd be a lens for them to understand how other groups are made invisible or marginalized, or oppressed. So I'm hoping that readers who get the book, your listeners will get a deeper understanding of Asian American culture and theology and understanding. But also, it will help them see how other groups of people are marginalized. So going back to how I wrote about my uncle, who we called Uncle Tiger, or in Korean, we said what I use. So that's a Korean term that we had. So my mother, that was four daughters and four brothers, and she was the youngest, the out of eight, she was the sixth child. And below her were two younger sisters. So this uncle Tynker, he was very, very scary. That's why every one of us, all the cousins, there must have been 35, or over 40 cousins, we all labeled him Uncle Tiger, because he was this our authoritative man in the household. And when causes met him, or when his, you know, siblings, when we got fat, when we had family get togethers, it was very clear that he was going to boss, his sisters, whether they were older than him, or younger than him. So my mother was younger than him. But I remember clearly how he kind of bossed around she was a grown woman married with children. And he, it was very clear that he still wanted to tell her what to do bossed around, and just make all of us all kind of scared of him. And my mother was scared of him too, because he was this authoritarian figure in her household. And that's very common. In many households. It's usually the father of the household, or the grandfather. But in my with my mother, on my mother's side, you know, we had this very scary uncle. But you see this in many, many households and many families in Korea, and immigrant households.

Randy 17:29

So you speak of how Asian Americans are perceived in America in particular, and how they're kind of relegated to these types or, you know, little, little boxes and you talk about how Asian American men are often emasculated within American culture, and how Asian American women are often kind of trivialized into pictures of submissive, hyper sexualized exotic beings. Can you speak to what that does for Asian American sense of self and identity in America?

Grace 17:59

Thank you for that question. So why women are portrayed that way, when Asians started coming? A lot, a lot of Asians came about 150 years ago to either work on the railroad. So you know, building the railroad, or they came because of this gold rush in San Francisco. So that's how many came and then and in Hawaii, many Japanese and Koreans went to work in the sugarcane, farm and other farming within Hawaii. So many people that came were actually men. So Asian men kind of came to the US. They thought, okay, they'll make some money, and then they'll go back home, they realized that it was very difficult to make money, they just assumed that when you came to us, you'll make a lot of money. But they barely survived with the little measly income that they were given either working on the railroad or digging for gold. On the railroad. There were other white people who worked. The white people were paid much more than the Asian workers. And they were also given free food. Asian workers had to pay for their food from the measly paycheck that they got. And also the dangerous work, you know, blowing up mountains using dynamite. The Asian workers were told to do that. So you already see this discrepancy and how racism comes into play, where many ancient many Chinese workers on the railroad died, building it across the US. So many workers were men. And then the few women that were allowed to come in, were then forced into becoming sex workers. And so right from the beginning, the portrayal of Asian woman or that they were the sex workers. They're here to please, white men. So that was kind of the stereotype that was given to Asian woman. And it has stayed on with us. That's how, when you watch movies, you know, the opera by the butterfly, or I guess the movie is? Yeah, Miss Saigon. The portrayal is this fragile woman. You know, Madame Butterfly, the butterfly is so fragile. So Asian women are portrayed like that, and also as sexual pleasers for white men and Miss Saigon, you have this white soldier from the US coming into Vietnam, and using this woman, this woman falls in love. But he doesn't disclose that he is already married, or to be married to a white woman. So you know, that typically, you know, that's a typical narrative that was portrayed for Asian woman and it has stayed on with us. For the Asian man, they were always portrayed as inferior, not strong, kind of feminine. And you see this in breakfast is, what is that? Tiffany's? Yeah, that movie and other movies where you're portraying Asian men as a clown, as someone who is this kind of masculine identity, very feminized. And that continues on today. And part of that is because we don't want other men to kind of dominate or make white men look bad, or make them afraid of the other people. So if you kind of feminized Asian men, than they are inferior to white men, they cannot kind of come and and kind of scare them off or threaten them because they are portrayed as this feminized masculine identity. And that continues on today to in social media. And, you know, in movies and other portrayals.

Randy 22:12

Yeah, I'm just interested at what that kind of objectification does to a person's identity and sense of self.

Grace 22:19

It really, it puts us down in so many ways as woman, because this objectification prevents society from viewing particularly someone like me as, oh, she can be educated and be a professor, or be an ordained minister, or be a scientist, or a mathematician, all those things. Because we have been objectified, we are viewed as sex workers. And this portrayal, you know, I write about the comfort woman in the book, too. So that was a huge atrocity that was done towards Korean, really young girls, by the Japanese. But it's this continual portrayal of Asian woman as sex workers to be dominated to be abused. And it's still all okay. Comfort Woman was happening during the war were Japanese kids that young girls, like 10 year olds, nine year olds, and maybe older teens, on the older teens were taken under the pretense that they're going to be working in factories. So many, many girls were taken. And they were used as sexual slaves for the Japanese soldiers. And when we think oh, okay, so sexual slaves, okay, they worked at night. This is the work that the daytime and they served. You know, many of these women have kind of written about it and told the public, many committed suicide, many were murdered. But the few surviving now there's only a handful of them in their 80s and 90s right now, but they said they served from 40 to like 70 men a day. So what that would do to a woman's body, or breaks your body apart. And that's why when many of them had diseases, they were murdered, because they didn't want to deal with the woman who were sick. So things like this, and when the American soldiers you know, they're still there in Korea. They set up these kind of little towns or townships. I don't know how you call them English, but they were places where the white American soldiers can go to bys sexual workers, and many of These women were murdered. It's illegal for for Koreans to have prostitutes, but there were designated. The government allowed this to happen in these designated kind of towns or these areas for the white American soldiers because it satisfied the and it brought in American dollars into Korea. So these things happened at a huge cost to Korean woman. And so, you know, that's happening in Asia. But then you see this also happening here, where they are objectified. And it has happened from the beginning of emigration. And it continues to happen today.

Randy 25:43

Yeah, the story that you told was the woman related to who, whose story you told who's of the comfort woman? No, no, it was shocking. I, you know, stopped and had to talk to my wife and was horrified by the story. It's, it's that part alone is worth purchasing and reading this book and visible. As you make a case, for the invisibility of Asian American women in the book, you really give us a history lesson on Asian immigration and Asian American history, can you just bring our listeners a little bit without giving away the whole thing into the systemic racism and oppression that Asian Americans have had to live in historically and presently in America?

Grace 26:23

So I think, because I grew up in Canada, when we talked about racism, it was just anyone who was not white, experienced racism. So Asian Americans, Asian Canadians, the aboriginals, the African Canadians, and the Latin X community. But hearing the US after I came in, in 2004, overnight, I realize that racism is talked about in black and white terms. So if you're if it's talked about black and white terms, anyone that falls in between, our experiences of racism are often ignored. Or white culture, white society will say to us, all that isn't racism, because you're not black. So even within the discourse of racist, so wait, you know, we experience it, you know, because our bodies are different, our ethnicity is different, we experience it continually. But when we share that these are experiences of racism, white dominant culture, many times, they will say that's not racism, and that that part itself contributes to the invisibility of Asian Americans, because our experiences are often ignored, or neglected, or just said, that isn't racism, but we experienced it all the time. And there's many different ways of experiencing racism. You know, I talk about xenophobia in the book. Xenophobia comes from the Greek word, you know, Zeno, meaning foreigner, phobia, meaning, you know, afraid. So we have lots of phobias here in the US. But xenophobia is being afraid of the foreigner, and Asian Americans, even though we could have been here for over 100 years, 200 years, we are still considered foreigners, for some various aspects. When African Americans, you know, they've been here a while to for many generations, and many of them have been here from the time of enslavement. They're not often called foreigners, they are just referred as African Americans. And I think the same would be with the Latin X community and the Native Americans. But for some reason, Asian Americans are continuously viewed as foreigners. So we are often labeled as perpetual foreigners. So even though we've been here a couple of 100 years, we will still be viewed as foreigners. And often people ask the question, Where are you from? That may be asked to an African American Latin X or Native American, but many times it's asked as oh, what city are you from? But for many, many Asians, the underlying notion behind that question is, oh, are you from Korea, China, Japan, Malaysia, those that's what they really want to hear. They don't really want to hear oh, I'm from Pennsylvania or from New York. Once I respond that way. As an Asian American, the asking No, no. Where are you really from? And that continues to perpetuation that we are these foreigners. We can never be an American and Asian. We're always Asian American, but we can never be a full American. Well as someone from Ukraine or from Portugal or somewhere from, you know, Western Europe and calm and They may not be able to speak English, because, you know, they may speak French, like many people in France do. We just think all of Europe speaks English, but they don't. There's Portuguese and Spanish, and French and Ukrainian. So what, but they can come to the US, maybe last month, and no one will view them as a foreigner. Because if you're white, and light skinned, and you're from Western Europe, you're just automatically Oh, you just have a beautiful accent. Oh, I love your British accent. Oh, I love your Parisian accent. It's so beautiful. Well, as someone from Asia, you know, who have lived here for a while, but still has this kind of accent. Nobody likes an Asian accent. Everybody loves a European accent, but they don't. And they will continue to say Oh, you are a foreigner, even though you may have been born here, or have been here as an immigrant for 20 years. So this perpetual foreigner, xenophobia. So if you're a foreigner, white dominant society will continue to be afraid of us. And you saw this during the COVID pandemic, you know, we had Trump saying, Oh, what did he call it? The What did he call it the Chinese flu or China virus, I believe at the time of iris and he, he had all these other crazy names for it. But he blamed and oftentimes, Asian Americans are blamed for when something goes wrong, because they're afraid of us, they think we're bringing the disease. And this COVID isn't the first time. There were other pandemics in the early 19th century, etc. And they often blame the Chinese. So you saw a lot of attacks against Chinese immigrants, when a disease started happening, and then they said, Of course, it's the Asians that brought it. So there's often a blame, this is the xenophobia. So there were all these different aspects, you know, the stereotyping the prejudice against Asian Americans. These are all the experiences of racism that we experience on a daily basis. You know, we are blamed for a lot of different things. And you know, my part of my task is to fight against this racism that persists here in America and beyond.

Elliot 32:37

Friends, before we continue, we want to thank story Hill PKC for their support. Story Hill. bkca is a full menu restaurant and their food is seriously some of the best in Milwaukee. On top of that story, Hill PKC is a full service liquor store featuring growlers of tap available to go spirits, especially whiskies and bourbons thoughtfully curated regional craft beers and 375 selections of wine. Visit story Hill pkc.com For menu and more info. If you're in Milwaukee, you'll thank yourself for visiting story Hill PKC. And if you're not remember to support local, one more time, that story Hill pkc.com.

Randy 33:23

You're leading right into my next question, Dr. Kim, I'm the son of an immigrant. My mom immigrated to the United States from Finland, when in 1968, when she was 19 years old, and she still has an accent to this day. One of my clear memory in high school was a girl calling my house, a girl who I liked. I answered the phone and said hello. After my mom gave me the phone, she answered the phone. In her first thing that she said to me was Randy, I didn't know that you had a maid. And I was so confused. I was like, What is she talking about? And then I was like, Oh, you think my mom's are made? Because she has an accent? Now that's my mom, you know? So as you were talking about this experience of watching your mom, you know, have trouble interacting in English and being immediately treated in a condescending way and in a inferior way. I know exactly what you're talking about. After seeing that dynamic with my mom where she's struggling to ordering at a restaurant is an embarrassing thing for my mom. You know, the thing that the difference about me being a Yes son of an immigrant is that I'm white, I'm European. So you never know that I'm a son of an immigrant and you'd never associate me in those terms. We like to think in America we have this romanticized version of ordination of migrants and immigrants. But not all immigration. immigrant stories are the same, right? Like we we European Americans like to talk about how Ellis Island everybody came in and it was great. And maybe we should go back to that. But that's not the same reality in the history of Asian American immigration. Can you bring us into the different story that Asian American immigrants have than maybe European immigrants with

Grace 34:57

the immigration app has been Europeans, I know they got on the boat and they came through Ellis Island. And when they came, some people did have papers. Many of them were, you know, fleeing the potato famine or some other famine. Many of them were weak, they weren't healthy. But they were processed immediately, there was nothing wrong. The people that worked in the immigration, they never held them back. So that is a stark difference from what happened to Asians that came through H Island. In San Francisco. So many boarded the ships. And they came to Angel Island, and many Asians that were coming, were mostly the strongest because you had to go in your own country kind of go through a rigorous physical exam, etc. So they only set the best people, the well educated and the physically strong people. Many of them had the paperwork when they left their own country. But in Ellis Island, they were treated like prisoners. They weren't processed quickly. You'll

Randy 36:05

island you mean? I

Grace 36:06

mean, sorry, in Angel Island, yeah, in Angel Island in San Francisco. So on the West Coast, versus the east coast, where the Europeans were coming in Ellis Island, when Asians were coming in through Asia Island, it was like a prison. Many of them were locked up for weeks, some for months, and some for years, for no reason. You know, the authorities that were working there just didn't feel like letting them through there were suspicious of Asian workers that were coming, even though they were the healthiest one and the most strongest ones. Versus in in the Europe, you know, in Ireland in other places where they were, you know, very there were fleeing the potato famine or other source, forms of famine or economic loss. They weren't always the strongest people, but they there was no question they were allowed in. So you see this right from the beginning, the difference, and how immigrants are process. We're all immigrants that are coming into this country. The only Native people to this land are the Native Americans. Everyone else, is an immigrant to one way or another, or brought here forcefully as enslaved Africans, or other means. They were brought here, but the only people are the Native Americans. But I think Americans somehow we have a short memory or amnesia, or something, we just don't remember our history. But I think it's really, really important to study our history. I raised three kids here in the US from kindergarten, all of them. And none of them learned anything about Asian history, Asian American history, they might have learned a little bit about black enslavement during Black History Month. But we don't teach it. And a few years ago, we held protests in New York, because New York has a large percentage of Asian immigrant population. And we want Asian immigrants history and, and stories to be taught in the public schools, just as we learn other immigrant immigration stories. I don't think they've actually put them in. But we continue to protest that because it's not part of our curriculum. So you know, you don't know it. But you're not the only one. It's never taught and in your adulthood, there are so many other things to learn and read. So Asian American history may be the last thing. So I'm so grateful for you to invite me on your podcast to talk about it and share. So thank you so much.

Randy 38:55

Yeah, I'm ashamed to say Dr. Kim that I don't know, Asian American history, I don't know the stories of the immigrants and, and all that even if as you were talking about Chinese men building the railroads and you know, blasting through mountains to make these happen. I remember in history class, seeing pictures of that happening. And the thing is, is that every one of those pictures was white. I don't I didn't see any, you know, Chinese or Asian, Asian men doing the work. Because if I'm not, if I'm not mistaken, they never took any pictures of them. They wanted to hide them. Is that right?

Grace 39:26

Yeah. And then there are a few you can find them online. But the fact that when we teach our history, we want to make them invisible. So this is the whole problem. Asian Americans are made invisible right from the beginning. The pictures of white man building the railroad was a very big narrative. But many Chinese were building that railroad and many many people died building it. But it's another part of the history you want to make us visit. or white society in general wants to make us invisible. Yes.

Randy 40:04

This idea of Invisibility is really kind of echoes in your book when you when you get into the autobiographical stuff, and you tell us in the book about what it was like to be a Korean, Canadian little girl in Toronto, and what it felt like to be in school and the depression, the disorientation, the silence, the invisibility, in many ways. Can you tell us I think, in America, we have this romanticized vision of immigration and, you know, everyone's coming to have this better life. And it's going to be as soon as you cross the border, it's going to be perfect life. Can you tell us about your experience in real life of what it was like to be a little girl growing up in schools, as a Korean Canadian girl,

Grace 40:45

I could see it was very difficult. You know, as a young girl, I started kindergarten, I didn't know a word of English, we never took English classes in Korea. You know, I just knew that we were immigrated. But as a five year old, you don't have any concept of what immigration means. And the impact it will have. All I knew was I was going to born a flight, and I was going to land in some different country. So starting kindergarten, when it's supposed to be fun and games, it's like the best time of your life before all the hard homework that you get. It was a difficult time. I see. You know, that was so long ago. But it's incredible how you remember certain things. And I remember being teased all the time. Even though I didn't know the language. I was teased. And I knew, because people are laughing at you making fun of your features. You know, they did the Poli, you know, and criss crossing. And, you know, they did all that. And I still remember and it wasn't just in kindergarten, it began in kindergarten, but it continued on. And it was this daily thing I had to fight. And I think I just internalized that, you know, I have to be better. So I really, really studied hard, I just wanted to be the top of the class. But even if you are the top of the class, I graduated top of the class, there is still racism because people just don't like you. Not because of your character, but because you just look different. And I grew up in a really small town, London, Ontario, it was called Wasp, I don't know if we use that term anymore white Anglo Saxon Protestant community. So you know, a few immigrants coming from Korea, to this predominantly white society, white, Anglo Saxon, Protestant society, it was hard. So I remember just, you know, going to the grocery store with my mother and people just making fun of us. They don't know who we are. But there's no need to make fun of us. But they do. So this continual racist actions towards us, is a very painful thing. And it's still part of your memory. And, you know, it still happens today. People make fun of, you know, my, my mother passed away, but my father's still alive. Because people know that they can get away with it. They know that Asian Americans aren't going to really fight, you know, physically or do something kind of, so people know that they can get away with it. So people will continue to make fun, mock us if they can, people still don't want to hear about Asian American theology. They don't want to learn from an Asian American theologian, let alone an Asian American woman. So there's a lot of battles that I still fight. So I'm always thankful for people like you who are interested and want to share about some of our struggles to learn. And to get a deeper understanding of theology and of who God is.

Randy 43:54

I can't wait to get into that portion of the interview. It's coming soon. I promise we won't go too long. But in chapter three, the the chapter on racism you say you were hinting at xenophobia? A little bit, but this the statement, you said the sentence that you wrote, just smacked me upside the face, you said, xenophobia is a defining feature of American life. Xenophobia is a defining feature of American left, I want listeners to sit with that, can you define you did it before but can you again, define xenophobia for us and explain your statement that xenophobia is a defining feature of American life?

Grace 44:26

I think, you know, xenophobia, afraid of the foreigner, we're always afraid of the foreigner. So I've talked about Asian Americans being the perpetual foreigner. Doesn't matter how many generations but then when we love migrants coming from the south, from the Mexican border from Central America, South America, we get afraid of this so called foreigners, we don't we don't want to let them in And because we are afraid that they're going to take all our jobs. So the xenophobia is part is so embedded in this American culture. But when we think about the migrant workers who come there all the jobs that none of us want, you know, nobody wants to pick tomatoes, all day long in the hot sun, or pick lettuce, or these hard labor, none of us have dreams of all we're gonna raise our kids to be cleaning toilets all day long. We don't want those jobs, but we still have this narrative, all my goodness are coming to steal all our jobs. So the xenophobia is this defining nature of this American culture. You know, we have refugees coming. And I think as a wealthy nation, we should be accepting refugees, whether they're political, refugees, climate, refugees, or socio economic refugees, but we're so afraid of them, that they're going to bring some disease. So I think this American culture, we really need to understand how we are acting and reacting, you know, as Christians, you know, when we studied the Bible, Jesus welcomed the marginalized, the oppressed, those who were on the outskirts, he talked to the Samaritan woman, you know, Jews and Samaritans weren't supposed to interact. He, even in the Old Testament, it's either there's all these verses and stories of the foreigner, and how you are to welcome the foreigner and, and be with the foreigner, and the foreign woman are also in the biblical passages. And God uses the foreign woman. And so the foreign and when we look at the lineage of Jesus, Jesus, the lineage is from a foreign woman. So God uses foreigners to somehow teach us different lessons. And I think if we kind of opened our eyes and see what is happening, how we are behaving and how our culture is reacting to foreigners, I think we should kind of sit back and kind of examine our own lives and Are we welcoming the foreigner, as God had told us to do? I can't remember that passage right now. But you may remember the passage better than me of welcoming the foreigner into your land because you were once foreigners, yourself. I think that is such an important passage for us. Especially at you know, America, a land of immigrants, land off foreigners have come. But somehow the white European immigrants have become the settlers have come to colonize here, the North American land, have become afraid of other foreigners that are coming into the land.

Randy 48:13

You're making me want to preach a sermon Dr. Kim, and I'm not going to do that. So you did very, very well.

Grace 48:18

I may start preaching if you keep asking me these questions.

Randy 48:22

You're doing it I love it. Talk about church stuff a little bit you you speak of the Korean church is both a place of refuge and safety, relationship, family, all the things that you need and just have to have and crave as a as an immigrant, but also a place of marginalization and oppression for Korean American women. Can you explain that reality for us?

Grace 48:45

Yeah, so it goes back to one of the first questions that you asked about the WHO oppressed, so but, you know, when I think about Asian Americans in the church, it's not much different from other women to because churches are male spaces. Traditionally, you know, the theologians, all the major theologians are men for the last 2000 years, they have created these doctrines created God as a white male god. So we are entering these spaces, these male spaces so it is difficult for many woman and particularly Korean, Korean woman back in Korea and also Korean immigrant woman, Korean American woman here. So in a way the churches are kind of these hubs for many immigrants because if you don't speak the English language, and you crave your Korean identity or culture, and white society isn't a safe place for many immigrants, especially the first generation immigrants, that the church is a place of right fuge to provide all of this. Well, my parents first emigrated the church was a place to find employment because it was by word of mouth. You asked one another, where can I work? Where can I find a job? Or how can I start a business? It was a place where immigrants all shared those information. And many of the Korean churches still today hold language, Korean language school. They're a Friday night or a Saturday or Sunday, where adults are many children can go to learn the Korean language and Korean culture. So it was this wonderful place and it still continues to be a wonderful place where it's not just a place of worship, but a place to socialize and learn and share and eat Korean food together. So it's a wonderful place. But then because of patriarchy, and Confucianism is also very embedded within the Korean churches, and Confucianism. Their model is obedience, so you know, a woman or to obey. So women are Toby three people, their father when they're young, their husband when they're married, and then when they become widowed, they obey their sons. So it's this complete obedience to men. And then, of course, in the Korean American churches, majority, I can't think of a Korean American church where the senior pastor as a woman, let alone any pastor as a woman. So you are to be obedient to the male minister, as you would your father or your husband or your son. So is this complete kind of obedience, you kind of listen and you obey whatever the Korean male pastor is saying? So in that kind of culture and society and the church, yes, women are then doubly marginalized and oppressed, and forced to obey. Yeah, so it's very difficult for Korean American woman. Yeah,

Randy 52:09

it's as if Korean American woman or you're almost Tripoli, marginalized, because it's in the world, the American world, it's an at home, and then it's at church as well. So Dr. Kim, let's finish our time by talking a little bit theology. Really fun stuff. In chapter four, you speak to the reality that we in the white American church have created a white male god who blesses our xenophobia, patriarchy and racism. You said, and I'm quoting you now, the maleness and whiteness of the Christian God needs to be dismantled if racism and sexism are to be eliminated. I'm gonna say that again. Just so are so everyone. That registers you said, the maleness and whiteness of the Christian God need to be dismantled. If racism and sexism are to be eliminated. Such a strong statement, such an essential statement for us to hear. Most of us say, racism and sexism should be eliminated. But you say if that's going to happen, the maleness and whiteness of the Christian God need to be dismantled, in order for racism and sexism to be eliminated. Can you expound on that? Can you explain that a little bit?

Grace 53:12

I'll explain it. But then I actually wrote a lot more about it. In the next book, when God became white. It was originally called, I submitted as whiteness. Because so much of this problem is rooted in whiteness. But anyway, I'll come back to your podcast, and talk about that one. But then they changed it to when God became white, because it's so interrelated. So when I do you know, when I teach theology, so many people think, oh, theology is that that that that important? or religious studies, you know, when College is the first thing to go, if there's no money left in the budget, it is the religion department and the philosophy department, which are usually maybe combined in small colleges,

Randy 53:56

my co host would have something to say about that about philosophy.

Grace 54:00

Yeah, so you know, because we think, Oh, it's not that important. But religion really, and theology really impacts how we see the world and view the world. So much. So it really determines our ethics, what we do every day, how we treat one another, how we come up with these laws, you know, we have right now about abortion laws and immigration laws. Are we going to go into war? You know, are we gonna get engaged in war? All of these things are determined by our own religious understanding and our theological understanding. It doesn't matter what religion it always has an impact. So we as Christians, how we understand who God is, even though the Bible is so clear that we are to love God and to love one another. Somehow, we just can't raid are all little laws. And I've heard so many sermons that I've preached on this so many times. But in our own minds, we say, okay, we can love, who we want to love, you know, so whether, if they're an immigrant Forget it, because, you know, maybe they brought a disease, or maybe they're going to preach or teach me weird things, or my kids. All of these things are affecting, you know, theology and religion has so much effect on us. So, if we continue to talk about a white male god, it will continue to perpetuate white supremacy, white privilege, and they will continue to institute racism, and patriarchy and sexism in the church, and as society, because in the Bible, it never really says God is white. I've never seen any passage that God is white. But when Christians continue to claim that God is white, whether in our theological mind, or how we portray God in our writing, and then, while the other default is how we portray Jesus as white, he was never white. He was a Palestinian Jew, probably very, very dark, probably black hair. And another podcast, I mentioned that, you know, he was dirty, so he must have smelled, and then the host got all like, why he got all surprised. But my point is, he is not who we have portrayed him to be for the last 2000 years. He's not this Emperor wearing this beautiful robe, white skinned, you know, pearly white skin, with blond clean hair with blue eyes, and perfect beard. He wants to straggly kind of homeless man. Because he wronged you, he didn't really have a house when he was doing ministry, he just went from one place to another. And I have low certain that he was dirty and smelly, even though another podcast host was really shocked by my statement. But I just got back from Palestine and and, and Israel. And today, 2000 years later, you know, better hygiene, better roads, better everything. But there's a lot of dirt roads, still. So it's really dusty. I remember, I took my daughter and I said after the day, we're just going to put all our clothes what we wore, and another separate day because I said it's really dusty. You know, today, but I can't imagine how dusty it was back then it was all dirt roads, people. And that's why you know, in the Bible, it talks about all these cleansing rituals when you go to a person's house, you know, with a water and clean, clean your feet and hands. In Korea. If you add to a person's house, or many of the homes are built, where the bathroom is right by the entrance, whether it be an apartment building or traditional homes, it's because you know, if it's dirty, you go in there and wash your feet and hands before you enter the house. Today, we still don't wear shoes in the home. So you know we want everything clean that comes into the house. But anyway, my point is we've made him white in the image of these white emperors that ruled the land, the Roman Empire, the Greco Roman Empire, and after that, you know, the white European theologians, the medieval theologians, the Reformation, phyllodes is all white. So God continues. So by default, Jesus being portrayed white, God is portrayed white and male. There are enough references in the Bible of God not being a man or male, but we have continued to portray him. And all of this is to say that if we don't dismantle this, it will continue to perpetuate racism, xenophobia, patriarchy, all these isms that we should not have in society, or in our church. It was us continue to have it and I think as church leaders as ministers, it is part of our task to dismantle racism and sexism. But if we continue to worship a white male god, it'd be very difficult to dismantle it because That white male god continues to tell us that there's a hierarchy of people. Yes, there's a hierarchy of gender and men are at the top and a hierarchy of people and white people are at the top. Yes. Because God is the white male guy. Yes. It's why theologian. It's overlapping with my new book coming out. But anyway, thank you for asking that question. I think it's an important one. And maybe your listeners may not appreciate it, but I think it's an important question.

Randy 1:00:31

I think they will appreciate it. Thanks. Yeah, no, I mean, this, the idea that our racism or xenophobia or sexism and patriarchal culture is a is rooted in our vision of God is such a sobering and staggering statement and thing to consider and hold. And I think it's absolutely true. You also say, this is just, I love the provocative things that you bring in your book, you say that Christianity in America follows the religion that should be called American unity, rather than Christianity. Just briefly, can you can you say what's behind that statement?

Grace 1:01:06

I think I was with Reverend Jackson, and he kind of used the term American identity. And I think I've adopted it. I can't remember if I said it first. Or he said, first, we're gonna say you said it first. Okay. I think it's because of this Christian nationalism. And just in America, we've created this Christianity, like I have gone to so many churches, where there's an American flag. Yes, on the pulpit. I don't know why there's an American flag. What is the purpose of the American flag? Or outside the church or somewhere in the church building? I don't understand this. It has nothing to do with Christianity. So I don't know why it's there. If you're gonna put a cross, yes, that is symbolic. And, you know, we recognize that Christ died on the cross. So yes, I see why there is a cross, or why there's a burning bush a picture of a burning bush or a stained glass window of, of Moses or things like that. But the flag, I don't understand why it's there. And it's in many churches across denominations. And, you know, so many churches celebrate July 4, and you know, I've critiquing this psalm, if you're going to use it in a way, that's not so I don't know, it's hard to talk about it. I'm both dual citizen, American and Canadian. But I think if you uphold that higher than the cross, higher than the Christian message, it's a very big problem. And that's why I call it Mary Kennedy's in so many ways. Christianity itself, here in America isn't so Christian, or the Christian message, in the fact that we have said, we will go into Iraq, in the name of God, we're gonna engage in war. And we're engaging in many wars right now, as a Christian nation, and so many Christians want it. I don't understand why. You know, Christ talked about, Blessed are the peacemakers. You know, the damage, we are killing people. And we're destroying the earth, every missile that lands, it's destroying people's lives, and destroying God's creation. There is nothing good in this. But we Americans, it's almost like this empire. We say, Oh, yes, we have to go in and kill God people. Everyone is a child of God. And if we can see that, we cannot see it for some reason. We think other people of color are born of a Lesser God. And this is common in America, in the Western world. So I think as Christians increased, told us to take care of one another to love one another. Welcome the foreigner embrace. You know, Jesus was healing the lepers. The lepers were those who were sent out, because everybody was afraid that you know, they're going to get leprosy from them. They were sent out of society. Jesus walked with them and cured that. If Jesus did this, we are to do likewise. But we cannot seem to the message found here in America the Christian message, I just it so foreign to me. So Fornes from scripture, yes, it's not Christianity, but American identity. And I think other people should just recognize it for what it is is because we go into war in the name of God, we kill people, we do all these things, and the name of God, which is not so Christian. Yeah,

Randy 1:05:13

yeah, I mean, all you have to do is look right now on Twitter, on Christian Twitter and see the rage against the Palestinian people in the blood thirst for for Palestinian blood to flow in in the Middle East and breaks

Grace 1:05:27

my heart. I just, they just bought one of the oldest churches in the world. You know what, if that happen here in the US, there'll be an uproar, if it was like the oldest church here in the US. But this is one of the oldest churches in the world, I think it's a third oldest church, in the entire world, just got bombed. And people sought refuge because, you know, you go into these buildings thinking they're not going to kill you. So it is horrific for me. I have friends there, many Christian Palestinians, you know, they are losing their lives. And, you know, when we think about it, Jesus was born under occupation. The Palestinians have been living under occupation for the last 75 years. It is, it is not what Christ wants. And it is so painful for me. And we go, you know, the Christianity here in America is not the Christian message that Christ has been teaching us it is really painful for me to see this happening in this world. I just, we just laugh there two days before the strikes happened. And it's just horrific for me to see.

Randy 1:06:58

Well, let's hope and pray that the American church gets delivered of America vanity, and comes to Jesus and becomes Yes, at the end of the book, Dr. Kim, you highlight four Korean concepts that you say can assist us in making the invisible ones visible. They're all beautiful. I really, really enjoyed them all. But the concept of chi, as a way of speaking and thinking about the spirit of God is for me, particularly beautiful and intriguing. Can you tell us about the concept of chi, and how we might see chi is a new yet ancient way of understanding the spirit in the vein of the Hebrew walk or the Greek pneuma. Tell us about that a little bit.

Grace 1:07:35

You know, when I wrote the book, I wrote so many bad things, you know, the negative things about racism and patriarchy. So I really wanted to develop something that was positive, because I didn't want to be a book of ranting of all these things that are happening to Asian Americans. So I developed the theology of visibility. So I use the four concepts to help develop this visibility so that we can make visible of those people who are oppressed. And because you mentioned Palestine, I think in today's world wide view, I think the Palestinian are made invisible. So I think we really need to work on this theology of visibility, that they are children of God. And their issues are important. They are created in the image of God. And I wish every American every person can see that, and of anyone that is oppressed, that we can see that everyone is, is created in the image of God. So when we think about chi, chi is an Asian term, that means spirit. And when I think about interfaith dialogue, every religion has a concept of spirit. So chi is not a religious term, it just means spirit, and their recognition that the spirit is within our bodies. And I think that's important. You know, I've always had students who do taekwondo, or Reiki or tai chi, chi, and Tai Chi is the same spirit. And Reiki means spirit, the energy coming from the hands, I think, when we bring that into the Christian concept of Pneumatology, of the Holy Spirit, it's a really helpful way to understand the spirit of God because I think with Western white male Pneumatology it the spear became more of a philosophical term. It was something out there nebulous. You don't know what the Spirit is. So many, you know, mainline denominations, we don't talk about the spirit on PCUSA. We don't read it rarely talk about the spirit, because we're so crystal centric. But if we want to talk about the spirit, the presence of God in the world, the spirit that created the world, we recognize that this spirit is also within us. You He said, that's a helpful way for me to end this conversation too. Because if we see the image of God, the Spirit of God in each other, in you, Reverend Randy, and in all your church members and all the people that listen to your podcasts, if we see the Spirit of God in the Palestinians and the Israelis, that how can we hate them? How can we say let's kill each other? Or in the Ukraine, you know, in other parts of the world, you know, the North Koreans are villainize. But if we can see that we are all brothers and sisters, that we cannot want to engage in war, killing and bombing and shooting. You know, here in the US the gun, you know, so many people die from gunshots. I think if we can see the Spirit of God the cheat in each other. And if you want to know more about she, most of my 22 books are on the Spirit are on cheese, you can get any other book. One of them is called spirit life. The other one is called the Homebrew Christianity guide to the Holy Spirit. Another one is reimagining spirit. So majority of my books are all dealing with the Spirit. So I hope you will get it because I do expand on this concept of Chase. I hope all your listeners can get invisible. And then any any other book of mine that deals with this spirit she

Randy 1:11:37

Yeah, I think they will, since reading this and this concept of she is spirit was so beautiful for me. And so it arrested me and it had me thinking all today about what are we missing in the American church from all the beautiful richness of the cultures around the world in the different pictures of the divine and the different, beautiful uniqueness about the cultures that are just full in the world. But yet we only have this American lens that we transpose and then we bring to South America or to Asia or to Europe or whatever it might be. What are we lacking in our vision of who God is when we only see God through our lens through the Americana D lens. So thank you for your work. So Dr. Grace Ji Sung Kim. The book is invisible. There's 21 other books that Dr. Jason Kim has written and we can't wait for your next one. Can you tell us again, what the title is? Well, the

Grace 1:12:32

one that's coming out, you know, soon is called Surviving God that's coming out in March 2024. I co wrote it with Dr. Susan Shaw. But the one I kept mentioning is called when God became white. And that's coming out May 7 2024. So two books coming out soon so we can invite you back anytime to discuss any of them or any of my other 21 books.

Randy 1:12:57

Great Jason Kim. Thanks for staying up late with us. And thank you so much for your work.

Grace 1:13:02

Thank you.

Randy 1:13:17

Thanks for listening to A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar. We hope you're enjoying these conversations. Help us continue to create compelling content and reach a wider audience by supporting us at patreon.com/apastorandaphilosopher, where you can get bonus content, extra perks, and a general feeling of being a good person.

Kyle 1:13:34

Also, please rate and review the show in Apple, Spotify or wherever you listen. These help new people discover the show and we may even read your review in a future episode.

Randy 1:13:41

If anything we said pissed you off or if you just have a question you'd like us to answer, send us an email at pastorandphilosopher@gmail.com.

Kyle 1:13:50

Find us on social media at @PPWBPodcast, and find transcripts and links to all of our episodes at pastorandphilosopher.buzzsprout.com.

Randy 1:13:58

See you next time.

Kyle 1:13:58

Cheers!