A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar

Mixing a cocktail of philosophy, theology, and spirituality.

We're a pastor and a philosopher who have discovered that sometimes pastors need philosophy, and sometimes philosophers need pastors. We tackle topics and interview guests that straddle the divide between our interests.

Who we are:

Randy Knie (Co-Host) - Randy is the founding and Lead Pastor of Brew City Church in Milwaukee, WI. Randy loves his family, the Church, cooking, and the sound of his own voice. He drinks boring pilsners.

Kyle Whitaker (Co-Host) - Kyle is a philosophy PhD and an expert in disagreement and philosophy of religion. Kyle loves his wife, sarcasm, kindness, and making fun of pop psychology. He drinks childish slushy beers.

Elliot Lund (Producer) - Elliot is a recovering fundamentalist. His favorite people are his wife and three boys, and his favorite things are computers and hamburgers. Elliot loves mixing with a variety of ingredients, including rye, compression, EQ, and bitters.

A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar

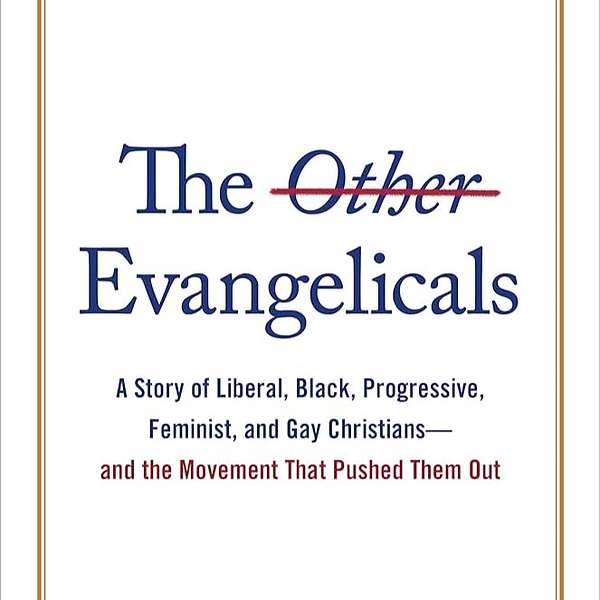

How Liberals, Progressives, Feminists, and Black and LGBTQ People Got Kicked Out of Evangelicalism

We discuss the history of evangelicalism with Isaac B. Sharp. Or rather, the alternative history of evangelicalism, for it differs in some significant ways from what you may have heard about how evangelicalism in America developed, and how most of us understand what it is today. Would it surprise you to learn there were once proud theologically liberal evangelicals? That there was a time when being evangelical did not obviously imply a conservative political stance or being white or straight? If so, Sharp's analysis in his book The Other Evangelicals will give helpful context to why that seems strange to us now (hint: it wasn't accidental).

The bourbon we taste in this episode is George T. Stagg from Buffalo Trace Distillery. To skip the tasting, go to 8:09. You can find the transcript for this episode here.

=====

Want to support us?

The best way is to subscribe to our Patreon. Annual memberships are available for a 10% discount.

If you'd rather make a one-time donation, you can contribute through our PayPal.

Other important info:

- Rate & review us on Apple & Spotify

- Follow us on social media at @PPWBPodcast

- Watch & comment on YouTube

- Email us at pastorandphilosopher@gmail.com

Cheers!

NOTE: This transcript was auto-generated by an artificial intelligence and has not been reviewed by a human. Please forgive and disregard any inaccuracies, misattributions, or misspellings.

Randy 00:06

I'm Randy, the pastor half of the podcast, and my friend Kyle is a philosopher. This podcast hosts conversations at the intersection of philosophy, theology, and spirituality.

Kyle 00:15

We also invite experts to join us, making public space that we've often enjoyed off-air around the proverbial table with a good drink in the back corner of a dark pub.

Randy 00:24

Thanks for joining us, and welcome to A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar. We've talked a lot about white Christian nationalism on the show, recently and historically, in the last three years, and the reason is, is because it's a very real presence and a very real problem in the church, we believe and today is another one of those episodes. We're talking today to Dr. Isaac B sharp. He wrote the book, the other evangelicals, a story of liberal black progressive feminists and gay Christians, and the movement that pushed them out. And Isaac is a he graduated from with his PhD from Union Theological Seminary. He's a very sharp guy, really, really eloquent and just fun to talk to. But I think this interview and I know this book, because I've read it is going to encourage a lot of people like us, or like me, in particular, I'd say, who don't like and don't want to have anything to do with evangelicalism don't want to be identified by evangelicalism. But yet, I still love the church, and I still want to place in the church, and I still want to fight for the church and be the church and embody the church. So the other evangelicals, it's not about what Christian nationalism, particularly, but it's got all the stuff that's bleeding into it.

Kyle 01:38

Lots of implications were and if you're the kind of person who still feels Evangelical, or thinks you are evangelical in some ways, but you feel like you've been pushed out of the church, you're not allowed to be any more a part of the group. This is a book for you. Because it turns out there is a century long, maybe longer history of people like you, who have solidly believed that they are evangelical, and that they are, for example, liberal or politically progressive, or African American, or queer, queer, fill in the blank. So it's, I mean, it's straightforward history. And even if you consider yourself a kind of moderate or even a little bit conservative, evangelical, and you want to learn more about the history, that maybe you won't read necessarily, and one of the more standard takes by somebody like George Marsden or Mark Noll, not that they're not great historians they are. But you're getting a version of that history. And it's leaving out some stuff. And you're gonna get another side of it in this book. So highly recommended. Yeah, and

Randy 02:31

I want to say if you find yourself on the more solidly evangelical side, or maybe even solidly conservative, evangelical side, or you're just kind of sick of people, trashing evangelicalism, this is a book that's hard to get around, because I said this about dummies book as well. And I think this is even more than dubious, because do me as a writer that brings in a lot of pop culture and all this stuff. This is a brilliantly researched book. And this is a actual historian who's put an hour upon hour upon hour upon hour, and you can get just keep on going on that into this research. So it's, it's something that I even if you do find yourself on the conservative end of evangelicals, and more just in the camp of evangelicalism, this is something that you should consider, because it's part of the history. And it's important to know our history. So we can learn from it, obviously, let's get to the interview first. But before we do the interview, we sample alcoholic beverages on the show, because we want to remind ourselves that we're trying to have conversations that we can have in a bar. So Kyle, what are we drinking tonight?

Kyle 03:30

So I have finally, after debating about whether I should bring the what, three years now I haven't had it for that long, but I brought you the best thing I own. I'm not gonna I'm not gonna tell you what it is right away. Other than that, it's a bourbon and just see what you think. I think it's the best thing Oh, and maybe you won't, I will not be offended if you think you've had better bourbons. I've also had three or four, maybe, possibly. But it's definitely in the top five for me that I've ever had got super lucky and found it on a shelf somewhere that shall remain nameless, and bought it at retail price, which it goes for literally 10 times retail price. So

Randy 04:11

in just in case, you're paying attention, there's a reason why Kyle brought this tonight for us to drink. And you won't know about the reason for another like six to eight months. But if you're paying attention to hearken back to this moment,

Kyle 04:23

we will so let me know what you think of this. And I won't be offended if you don't love it as much as I do.

Randy 04:28

It's like, like, you can smell a classic bourbon. I feel like you can smell like what this is what bourbon should smell like. Yep,

Elliot 04:36

like caramel color. Like nothing surprising there. But the legs maybe it's just my glass was a little wet because I rinsed it but it Like the droplets separate it's running in. In a stream.

Randy 04:49

Yeah, it's got Oh, Cooper's got honey, it's got caramel. It's got everything you want in the nose of a bourbon

Elliot 04:59

cereal.

Randy 05:05

That's crazy. That's crazy. Oak, citrus spice, cinnamon nutmeg. It's so complex with

Elliot 05:18

a mouthfeel like maple syrup. I love that just coats. What do you get?

Kyle 05:25

I get all of that. I mean, it's definitely a punch in the face proof wise, which I love to, you know, immediately it's barrel proof, whatever it is. It's got a depth and complexity of flavor that's hard to match and most bourbons. I mean, it has the flavor profile I really love. It's definitely in the darker in the richer and if there's any fruits, there's their dark fruits. There's nothing really floral going on here. And I appreciate bourbons that have that but this is not that. It's definitely on the lower tonal end of the bourbon spectrum, which is where I gravitate to. It just has a lot of heft. I mean, it feels like a serious bourbon describe.

Randy 06:02

I still do get that like citrusy bright note to it. It's dark, hefty, all that stuff, but it's got a brightness to it a little bit. That full spectrum is part of what makes it very obviously something that would be on the higher shelves. Alright, spill the beans.

Kyle 06:15

So this is George T stag. There it is. Yeah, so we previously I don't know if you remember this. We had Stagg, Jr, which isn't called that anymore. It's now just called stag, way back. And we loved it. I do remember him. And this is its big brother, essentially. So this is average, maybe 15 years old. It's a little bit different each release. This is a member of one of the flagship members of the antique collection from Buffalo Trace. There's five of those. Yeah, would you

Randy 06:41

say this is regarded by bourbon fishing autos is like second best, Pappy.

Kyle 06:45

Yeah, it's up there. Yeah, yeah. And some, some people will say some people prefer antique bourbons to pappy because pappy has kind of a unique flavor profile. It's a weeded bourbon. So it's it's very old. And so it has a very distinct flavor that not everybody in bourbon loves. So this is a more traditional bourbon.

Randy 07:03

We just mentioned I've had two old rip, which is a puppy variety. Yeah, that I didn't love. I've had other puppies 1518 years that were obviously good. But the 23 years just in a hole. Yeah,

Kyle 07:15

it is. It is you can't compare that there's, there's some that happens. And bourbon once it gets past the 12 or 13 year mark that it's rare that it's good at that stage because just the terroir and the weather and Kentucky's not really set up necessarily to age whiskey that long and you lose so much of it. By the time they they bottle this it's less than half the barrel left. And so I mean, you have to really know what you're doing and have something going right in your wheelhouse. And so most of the really well aged stuff comes from just a handful of places in Buffalo Trace is one of those.

Randy 07:45

Well, this has been a decently long tasting desert. Because this is one more time

Kyle 07:51

George T stag. Thanks for sharing it.

Randy 08:09

Well as extra Welcome to a passer and philosopher walk into a bar.

Isaac 08:13

Yeah, thanks for having me. I'm very excited to chat with you guys. Tonight.

Randy 08:16

We are too. So your book is the other evangelicals, a story of liberal black progressive, feminist and gay Christians and the movement that pushed them out. That's a mouthful and provocative right out of the gates. Tell us about yourself, Isaac, and where this book came from.

Isaac 08:33

I am Isaac sharp. I work here at Union Theological Seminary. I'm in fact, in my office this evening. I graduated from Union with my PhD in 2019. And have worked in various roles here. Since that points in that same stretch of time. I also, as you all may now be aware, published this book, which is based in part on my dissertation, the import part, it is definitely based on my dissertation. But when I say based in part, I mean, it is part of my dissertation. Though it may be may be impossible for some folks to believe when they look at the page length of the book, the dissertation was actually a bunch of longer projects, there was this kind of sprawling look at all of these categories, and at least a couple more in 20th century evangelical history. So this book was an initial attempt at carving out a kind of digestible chunk of the dissertation. And I hope that I have done that, focusing on some of the what I think are in one way of reading the story, some of the most kind of determinative chapters of the 20th century evangelical story, so that's a maybe too, too long winded way of answering a simple question.

Randy 09:49

Now it's perfect. I mean, it's such a complete it feels like a complete history of evangelicalism, which makes me want to know what the chapter Yeah, what did you cut out? What did we miss out of this dissertation?

Isaac 10:00

And so based on some of your your all's, like showing of the hands of your hands with the a bit of what we might end up talking about today, you you may have been interested actually in the major Chapter The get carved out. So the biggest portion of the dissertation that didn't make it into the book was a chapter that it made it in a little bit in the introduction and sprinkled throughout. But there was a full 100 page plus chapter that was looking at the history of Armenian Wesleyan PYtest traditions in evangelicalism and how those kind of cluster of evangelical types of traditions lost out in essence to the more reformed Calvinist or fundamentalist groups, and looking specifically getting into some of the weeds of debates in quote unquote, evangelical theology proper, kind of in the the depths of some of the debates in places like the Evangelical Theological Society, and some of my editors, Edmonds, perhaps wisely, figured that in looking to a broader audience, and hoping for a broader readership that some of those in the weeds debates about Calvinism versus freewill in evangelical theology might be a little much for readers of a book that's already this long. Yeah. So there's this big chapter that is looking at that kind of evolution and evangelical theology that ends up kind of leading up to a high point of how the kind of Neo Calvinist reformed stuff took over, essentially, evangelical theology. And the other chapter that I had to just condense and squash into a related chapter was there was a whole chapter about Carl Bart and party and evangelicals across the 20th century. So some of the deep weeds of evangelical theological debates are what ended up not making it in

Kyle 11:57

probably the right call. But I also have questions about both of those things.

Isaac 12:01

And we can talk about that. And there may be some, there may be some work that comes out of that at some point, we'll see.

Kyle 12:06

So when you look at the table of contents, or even just the subtitle of the book, you have chapters on liberal evangelicals, black evangelicals, progressive evangelicals, feminist evangelicals, and as you put it gave and delegates are LGBTQ evangelicals. So it struck me that a conservative, picking up your book and looking at the table of contents might think those are all the same thing, and close the book and put it down. So can you briefly explain emphasis on briefly because this is a huge question, your choice of topics or perspectives to include? And also What's distinctive about those types of evangelicalism from each other? And What's distinctive about their critiques of what became what we all know as evangelicalism?

Isaac 12:47

Yes. So it is certainly the case that there are different ways one can slice in the abyss. And there are folks that I feature in various chapters that could have potentially gone in other chapters, and they might have had overlap in either the groups and they moved in constituencies that they were a part of, or even issues arounds, theological commitments or more, more concretely, things like questions of identity, personal identity, racial and ethnic identity, sexual orientation, these kinds of things that there are folks who had potential overlap in various chapters who could have gone in another chapter. But slicing the puzzle, the way I did is, I think, was justifiable in a in a variety of ways, based on sometimes folks primary work, or their kind of primary self identification, at least for the periods I was looking at. So that was another kind of balancing game where I wanted to feature certain thinkers, because of their contribution arounds, debates about evangelicalism and race or evangelicalism and gender identity, and a balancing act between that and kind of periodization, where it's kind of moves in waves, these things move in waves throughout the 20th century. And there's also overlap in time with folks. So roughly speaking, the chapters also kind of move chronologically, and I try to build it up that way. So some of the answer is I tried to go with the category of arguments or flag that someone plants that ended up being most central app, the periodization I had to use, but there are certainly other ways of slicing the puzzle. And to your point, there is the potential for certain kinds of readers to just paint all of these things as as different kinds of liberal for instance.

Kyle 14:55

Exactly. Yeah. are different kinds of progressive but they're not right. They're very different. it and one of the great virtues of the book if the reader is interested enough to stick it out for almost 200 pages, or whatever it is, is discerning just how different they are and just how different their critiques are, for example, the liberal critique and the black American critique very different, sometimes incompatible, in some ways. So

Randy 15:19

yeah, in for listeners sake, can you tell us the difference between liberal and progressive Christians?

Isaac 15:25

Yeah, so this piece in particular is an important distinction and ends up becoming a piece that a lot of folks want to push from a number of angles, right. So the distinction is important for a number of reasons, one of which is the liberal evangelicals, that first chapter and I say I've said this a few different times in a few different places. But I think it is worth repeating, potentially, for your all's audience that any one of the chapters could vied for the most controversial, depending on who the reader is and what the context is. But the first chapter about liberal evangelicals, certainly, in certain contexts could be at the top of the list of most controversial because I am doing something that is distinctly different from most histories of evangelicalism, which is, and so this is another winding way of answering the question about distinction between progressive and liberal. What I'm doing this a little different is making an argument about the fact that evangelical identity in the 20th century was not as self evidently tied to certain traditions as it was later as it later became, or as historians later painted it, such that for a period of time back to the early 20th century, when there were these things called the fundamentalist modernist controversies and kind of divergence between two traditions in American Protestantism, between the liberal mainline and the conservative evangelical tradition, that generally speaking, historians talk about that divergence as pretty distinctive and definitive. And that shapes the 20th century evolution of Protestantism. And there's something to that. It's not entirely inaccurate. But part of what I'm doing with that first chapter is making an argument about evangelical identity and the fact that was Messier for longer than folks realize. Such that you get some folks who and this is I promise, I'm gonna land this plane. Now, folks who would identify themselves as liberal, as Christians who are liberal theologically, who would identify with liberal theology in some capacity. And by that it can mean a variety of different things. But a couple within the context, that would mean would be willingness, for instance, to embrace Darwinian evolution, for instance, and or higher textual criticism of the Bible as tools that are possible to be appropriated within one's faith and still be a faithful Christian. And so this is the divide among the kind of fundamentalist modernist controversies. And you have these folks who fall on the quote, unquote, more liberal side of things, who would have said things like, we can potentially entertain the idea of Darwinian evolution with certain readings of Genesis that are not necessarily literal readings that treat the early chapters as a scientific textbook about six day creation, and or can use historical critical methodologies to better understand the Bible without sacrificing our Christian identity and for some, specifically, their evangelical identity. So you get these folks who are identifying with what became known as liberal theology, who also said, No, we are evangelical, and by that many of these folks will mean something like we're still faithful to the gospel. So the good news, the message of, of Jesus, progressives, the evangelical progressives, which is a later chapter, and emerges later in the 20th century context, tend to be folks who would reject some or all of liberal, theological traditions, or at least what I identify with, quote, unquote, conservative theology, evangelical theology, affirmations of the authority of the Bible, and or inerrancy of the Bible, but who interprets that inerrant Bible as having political implications that fall on the progressive side of the spectrum. So this is that was an extremely long way of answering chapter one liberals is talking about liberals more Theologically speaking. And the chapter on progressive evangelicals is talking more exclusively about politics. Yeah,

Randy 19:29

it's why I love history so much, because I was I was reading the first chapter about the theologically liberal, and I'm using scare quotes because it's just so timely liberal. But people like who was it Harry Emerson? Fosdick. And did I get that right? Yeah. All right. I don't want I don't want to be made fun of. And Charles Briggs and others who were having the same arguments 130 years ago that I'm having now whether it's about biblical inerrancy about science, evolution, historic critical approach to the Scriptures. This is not new. And that's so encouraging and beautiful to me. That's why history is so cool.

Isaac 20:08

Yeah. And that in particular, actually, that's a that's a excellent segue to a point about why I ended up including that chapter. And one of the reasons I did is this thread that I traced through several of the chapters, actually, that is an example of debates that are recurrent across a 20th century evangelical context, I wanted to include that chapter in particular, because of that, right? So as an example, you get this thing that happens among 20th century evangelical thinkers, where it will seem settled for a generation, that evolution or this question of science, right, and integration of science and faith is a settled matter in evangelical circles, right? Even the idea evangelicals are not embracing evolution. And then 10 years later, there will be a new debate, that is essentially the same debate among a new generation of evangelical thinkers, that is re litigating very much the same debate. And so including that chapter was in some ways, was motivated by this idea that these these quote unquote, liberal, you know, liberal trends that what get called liberal trends in theological discourse, like embrace of some sort of higher critical methodology, or, you know, acceptance of some sort of Darwinian theory of the evolution of species, that these things kept recurring in 20th century evangelical circles is like almost like clockwork, like along, you know, some events along like every 10 years, that happens that this debate happens again. And so that was an example of something that I do try to do throughout the book, that is show that many of the current debates in evangelical circles happened a long, long time ago, and that there were folks on quote, unquote, both sides of these debates going back decades. Yeah,

Kyle 21:56

you did a great job of it. Yeah. Randy found that fact encouraging and beautiful. And I found it frustrating. And, sure, sure, just depressing. I mean, because you just like that, on a practical level, like nobody reads books written more than 50 years ago, like almost nobody. And that includes scholars too, because you can't publish on something that's been beaten to death. And so we're just doomed in the cycle to say the same shit for every 40 or 50 years. And that's very depressing. And this book brings that up nicely.

Isaac 22:25

I won't let it I'll try to keep us from going too far down the rabbit hole on this one. But a recent example of this in kind of, like online discourse that I've seen is, there's this like continuing effort to basically do the same thing that J Gresham Meechan did back in the early 20th century, and Meechan was this fundamentalist figure who wrote this book, arguing that liberals are not Christians, essentially, that liberalism is a different religion. And you get that selfsame version of that arguments in books that came out, you know, a couple of years ago now, within the last two years that are making arguments about like Christianity, and, you know, wokeness, how they're different religions. And it is essentially just a like, reconfiguring of J. Gresham, Mason's argument that he made all the way back in the early 20th century. So yeah, that's it is, can be frustrating, and or encouraging, depending on your perspective, but definitely fascinating. Yeah,

Randy 23:21

that's us encouraging.

Kyle 23:24

That's like kind of sums up our podcast. She's encouraging. Okay, so let me ask a quick follow up. That's not on the outline, because I'm interested in it is related to something that will come up later. So you said for like the liberal Christians, for example, the sense in which they were evangelical is that they really cared about the gospel. But that's not distinctive to evangelicalism. It's not distinctive to any Christian tradition. I know lots of Catholics who care deeply about the gospel. I know lots of Lutherans who do and Eastern Orthodox people who do and on and on and on. So, and this is going to relate to a question I have later about the slipperiness of the word Evangelical, it seems like it can mean almost anything depending on who's using it. And at a certain point, it makes you wonder, is anybody evangelical? Or is there any sense in trying to figure out what this means?

Isaac 24:12

This is a fascinating question. And it's, it is definitely the case that one of the complicated questions in debates in scholarship about evangelicals, but also among kind of, you know, insider debates among evangelicals is this distinction question, right? Like what makes an important that's the, this the task of the whole book in some ways, so I definitely relates to anything we'll talk about because this is part of the argument that I'm making, that because of the nebulous nature of what it means to be evangelical or or how to define evangelicalism, or even classifying what it is right isn't a movement, a tradition of theology, an aesthetic, a, an idiomatic, you know, in group cultural kind of distinction. There are all these ways of slicing it's that it does become an interesting question what makes evangelical Christians different from other Christians? Part of the argument of the book is that there was this concerted effort on the part of those who claimed evangelical identity to make that distinction very hard to make it very clear that we evangelicals are different from other Christians. And in fact, I don't know if I say this explicitly, but I've I've summarized parts of the book in a gloss that other in other places, discussions, and maybe even just online spaces, or tweets or something, that one of the functioning of one of the ways that evangelical gatekeeping has functioned, I argue, is as a way of designating, you know, quote, unquote, true Christians, we evangelicals are the real Christians. And all those non evangelicals are the, the heretics or backsliders, or outsiders or what have you, whatever your preferred designation of, to, you know, cast aspersions on somebody's faith is and that that has been one of the functioning, one of the ways that evangelize identity has functioned. Even in actually the liberal evangelicals chapter, you see a bit of that prefigured in the way certain folks used evangelical to mean to include certain kinds of liberal theology, but not other kinds of liberal theology. So you get these, this distinction that emerges, and it's all but forgotten now, in the kind of historical record of like an evangelical liberalism versus other kinds of liberalism. And one example of that distinction making with some of the quote unquote, liberal evangelicals was to suggest that we evangelical liberals are different from say, Unitarians. Yeah, right. Those Unitarians are just in it. You know, this is this would be the some evangelical liberals, they're just anything goes. And we evangelical liberals are still holding on to something distinctive about the gospel. But to, to the question about what makes that different than, you know, say, Catholic Christians or Eastern Orthodox Christians? That's a That's a great question. And is a a perennial one for anybody who's interested in this question of identifying as Evangelical, right, like, what does that mean? And what does that what does that distinction mean? It's important the task of the book.

Kyle 27:13

Yeah, good. I'm gonna have more about that later. So let's put a pin in it. But I want to ask you about historiography a little bit. And particularly the group that you call the new generations of historians of evangelicalism, I forget what chapter that is, but people like George Marsden and Mark Noll, and a couple others that I hadn't heard of carpenter hatch, etc. So they're evangelicals, writing evangelical history, I've read No, I've read a little bit of Morrison and they do it really well. Like they're, they're good at it. It's believable, speaking as a very much liberal, non Evangelical, it's still like good history. But their role in defining what evangelicalism came to mean was something that I had never thought to question, and how it might have probably unintentionally pushed out some other kinds of perspective. So you mentioned people like Donald Dayton, for example, who had a very different take on the history of evangelicalism. So can you speak to both how they're put them in a category that they can put them in their the kind of Reformed category? And, you know, complexify that if you want to, but how their view came to be kind of the standard view of the history of evangelicalism? And then where are you trying to situate yourself in that conversation?

Isaac 28:28

This is another of the deep in the weeds questions that I find fascinating that I will try to make as lively and interesting for listeners as possible. Let me

Kyle 28:37

let me make it a little, a little more concrete, just just a take home point that other people might also care about. So one of the things Knoll is famous for is saying that evangelicals have a big anti intellectualism problem, right? Yeah. And I was very persuaded by that. Because all the Evangelicals I've ever known had a big anti intellectualism problem. Yeah. And so but maybe that's part of his tradition, and that he sees it that way might just be because he's ignoring all the Wesleyans. So Right. So how do we how should we read historians who make claims like that, given that they're coming from a kind of not parochial, but a particular tradition?

Isaac 29:14

Yeah. So this evolution of the kind of history of Eve of history of the histories of evangelicalism is so fascinating, because I use it as the kind of table setting early thing in the book to lay the groundwork for how we got where we are with this kind of like constant discourse about evangelicals. Right? And you know, this book is my book is a contribution to that. This like ongoing wave of wave after wave of fascination and discussion with evangelicals. And so part of what I end up tracing is that this really interesting thing happens across the 20th century in academic settings, and specifically in the kind of professional and academic study of history. And it is this like interesting development Were evangelicalism as a category or as a movement gets ignored for a long time across 20th century historical work. And in the early 80s, you get this emergence of these folks like Marsden and Noah, who basically end up offering supply for a rising demand of interest in evangelicals that comes on the tail of Jimmy Carter in 1976, saying I'd been born again. And then the rise of the religious right, you get all sudden folks are interested, like, what is this? What is it? Where did all these evangelicals come from? Right? Like, who are these people? Where did they come from? And you get this first generation of, of what I call, you know, the early evangelical historians like Morrison and all who come along and writes, they meet the rising demand with supply by writing these fantastically well done rigorous thorough histories of a tradition that they have some relationship to, right. So this becomes an interesting phenomenon over time, in that you also get folks like, for instance, Randall Ballmer, who would maybe be an example of like an early ex Evangelical, right, so you get other historians who were perhaps once a part of the evangelical tradition, who no longer necessarily identify with it, because of what it became and that this is a part of the story of the shaping of evangelical history and so to the mores than in Dayton thing to see if I can do a quick gloss on that without getting too far in the weeds, mores that folks like Marcin and no end up setting the kind of canonical account of the evolution of even contemporary evangelicalism, out of fundamentalism with precursors and fundamentalism and the evolution across the 20th century of the Neo, the quote unquote, Neo evangelical movement as the kind of mainstream version of evangelicalism. And their history is exactly right, in one in one way of rendering the story that is the centerpiece story of what became mainstream evangelicalism in the 20th century. That is the case. But part of what I am trying to do is to suggest in a slightly different way than what Dayton would be doing, but to it, but in a similar kind of poise to say that the story is more complicated than that story. And one of the questions I was wanting to ask is how the mainstream version of the story became the mainstream version of the story, right? Like, it's not just self evident, someone steps out and says, yes, here is mainstream evangelicalism. And this is the story we're gonna tell right? Like that had to happen over time. Right. So part of what I suggest is that historians had a role in focusing on the evolution of Neo evangelicalism, they're centering something in the evangelical story. And in that story, I suggest there are perhaps smaller players and less well known players that also affected how that mainstream version became mainstream. Yeah, I'll loosen up. I'll pause there in case that slightly gets at the kind of it does. kind of question you were asking.

Kyle 33:02

It does. But thank you. Yeah. And I think it's a good segue into Randy's next question, because Surprise, surprise, a lot of that story has to do with certain groups of Evangelicals actively pushing out other groups of evangelicals. That's kind of what Randy is about to ask about, I think.

Randy 33:15

Yeah, so I mean, it's almost like we have an outline that we're almost

Elliot 33:28

friends before we continue, we want to thank story Hill PKC for their support. Story Hill, BK sees a full menu restaurant and their food is seriously some of the best in Milwaukee. On top of that story, Hobi Casey is a full service liquor store featuring growlers of tap available to go spirits, especially whiskies and bourbons thoughtfully curated regional craft beers and 375 selections of wine visit story, he'll be kc.com for menu and more info. If you're in Milwaukee, you will thank yourself for visiting story Hill PKC. And if you're not remember to support local one more time, that story Hill pkc.com.

Randy 34:11

One of the things incredible to me in this book is how fantastically and depressingly consistent evangelicalism has been from the jump in that two areas. First thing that I want to hear from you on is that we're evangelicals have been known more for who and what we are against or they are against than who and what they're for. And you even quoted the founding statements or the Constitution or whatever of the national Evangelical Association, which I think came together in 1942. And I've got three exclamation points by this by this line says, this is in the bylaws or something it says we realized that in many areas of Christian endeavor, the organization's which now purport to be the representatives of Protestant Christianity have departed from the faith of Jesus Christ. How, like, just completely laying waste The whole tradition of Protestant Christianity. That's the way evangelicalism started, and its formality as the National Association of Evangelicals formed. And it was before that, I think probably too, right? Can you explain to us this first inclination of who we're against?

Isaac 35:16

Yes. So this is a fascinating question on the longer arc of the history of evangelicalism, and one that I had to bracket a little bit. So this question of how far back you can trace evangelical history is a really complicated one, as well. And for the book to not be, you know, 2000 pages, I had to set some boundaries and so on the 20th century context of what is what I end up doing, and what I ended up arguing is, regardless of if there was something called the evangelical tradition, going way back, you know, back into previous centuries 19th 18th, that in the 20th century US context, something different was happening with this question of evangelicalism as a movement in evangelical identity. And to a previous point that we were discussing, one of the different things that I argue is that it becomes this kind of proprietary trademark name this brands that a certain group of conservative Protestants, Christians in the US context claim as a way of differentiating ating themselves from other Christians, by suggesting, in effect, that we are the good conservative Bible believing Christians. And we had to establish these organizations because all of the rest of the Protestant, you know, inter denominational organizations and the the the powers that be in Protestantism at the time in the mid 20th century, are heretics, right? Like this is made pretty explicit if even if not using the language of heresy, using the kind of language you describe with the National Association of Evangelicals that says, ever we look around. This would be the you know, kind of the architects behind evangelical identity in the 20th century, the post world war two Rise of the Neo evangelicals, the folks who established organizations like the in a said things, you know, this is glossing and summarizing, we look around and we see no real faithful Christian leaders left, and we got to start something to be a counter example of good faithful Christianity. And what they called it was evangelical. And it was explicitly this is this is I'm so glad to ask this question, because this doesn't come out. And some of the interviews and this is an extremely important piece of the 20th century evangelical history, especially as it relates to current debates, right of the same group out group stuff. Yes, it is the case I argue that what became mainstream Evangel identity in the 20th century context was explicitly established as, as a what we're against move. We good faithful evangelicals are against those backsliding, mainline Protestant liberals who are heretics and socialists and you know, whatever, whatever else they could use to label and you see it in the establishment of groups like DNA, which is explicitly a counter to groups like the emergence of like the World Council of Churches that medical movements, Christianity Today, explicitly founded as an alternative to the Christian century, fuller Theological Seminary has something in its language. That is a similar kind of, we looked around and could see no faithful interdenominational Christian seminaries. And so we had to start one. And so that differentiation to the previous point we discussed, it's baked in to 20th century eventual identity that this distinction that evangelicals are the good real Christians and everybody else on the outside are the not are the questionably Christian Christians that's baked in there from the early rise of this inter denominational movement.

Randy 38:55

Yeah. And similarly, the idea of ecumenism being like to me, like humanism was a huge virtue. And I was a good evangelical when I started my church, you know, 15 out of 17 years ago, and didn't didn't seek out ecumenical relationships in collaboration, all this stuff, and now it's my heartbeat. And that's because I was a good Evangelical, I didn't care about humanism, I cared about us and our people. That's been happening since the beginning. It seems like as well, right.

Isaac 39:23

Yeah, that's it's such an interesting aspect of 20th century and into the 21st century evangelical history because it is definitely the case that what became the mainstream version of movement was formed as a an anti ecumenical enterprise right that Ecumenical Movement is dangerous for a number of reasons. One would the one that some would suggest evangelical leaders would suggest, you know, watering down the gospel or things like getting into some of the I didn't do too much of this in the book, but looking at something like dispensationalism and eschatology, this idea that the act A medical movement is somehow tied to this idea of a one world church that maybe is based on a certain reading of the book of Revelation. And so you get that anti ecumenical impulse. But also and I didn't get into too much of this either. The view among certain conservative evangelical leaders and gatekeepers in mid century that the Ecumenical Movement was to, not only to liberal theologically, but to progress, you know, artificial distinctions here to progressive politically, as like you get scholars who have argued persuasively I think, that another aspect of shaping evangelical identity a 20th century was this tied to like big business and corporate interests and anti New Deal ism and free market ideology. That's I didn't get too much into that stuff. But that also is definitely related to this like anti ecumenical impulse. The interesting thing to me is in a difference, it aside from just the Ecumenical Movement and a different understanding of what it means to be if you zoom out to a more general kind of inter denominational cooperative efforts, right, if you took take that as like one of the one of the bases of the Ecumenical Movement, evangelicals become a very inter denominational, a cooperative enterprise across the 20th century, just two very different ends than the you know, quote unquote, mainstream mainline Ecumenical Movement. Yeah,

Randy 41:20

yeah. You mentioned Christianity today. And Kyle beat me to it sometimes when we read well, Kyle is always first to the outline for us. And there were two words that were littered throughout your book, and that's Christianity Today, I wound up just like circling them every time I saw two words, and it was like twice a page. La Kayo s the rest of the question, but I was so struck by how much of a presence Christianity today had in this book.

Kyle 41:46

Yeah, particularly though, like, what has its trajectory been like, and how, what role is it played in normative Ising? What we've come to know as mainstream evangelicalism, the type that you've just been describing, and where do you view its place? Now, visa vie that kind of evangelicalism because it's, it's, it's, it's transformed quite a bit. But there's still seeds. I don't want to give my cards away. But I want to take

Isaac 42:08

Yeah, this is. So let me think about how I want to take a run. There's a lot just dropped in that question. Christianity a day has been a gatekeeper trendsetter for the evolution of this evangelical identity that I'm talking about as the kind of like centering where who gets published in Christianity today has a powerful effect on what is is theologically socially politically acceptable in evangelical circles, right. So an example that I end up talking about in the book that is one that I had never died only seen talked about in like, passing articles here or there, but never really seemed like a full on reckoning with until maybe some beginning recently, Christianity Today emerges very close to the same time of the emergence of the mainstream civil rights movement in this country. And that's an interesting opportunity historically, because the early framing of Christianity Today, under the guidance of initial editor, Carl Henry, was to suggest that fundamentalists had gone too far in becoming too sectarian and too walled off from the broader social world and social problems, and unwilling to engage with the broader culture. So what an opportune time for the emergence of Christianity today in the context of the emergence of mainstream civil rights movement, and you get this fascinating thing that happens, where there's little to no engagement for a long period of time. And then when the engagement comes, it ends up being this initially ends up being this kind of both side or thing where you have Christianity Today, platforming segregationists who are making arguments in the pages of Christianity today of why Christians must support segregation. And that is, I think, that has a normal devising effect on what is acceptable discourse for quote, unquote, official evangelicals, right, like fast forward today, it would be unheard of one would imagine and unthinkable for Christianity today to be featuring kind of, you know, some far right Neo segregationist, which is a sentiment that's like on the rise in this country. But there has been, to my knowledge, a little reckoning with that history on the part of the magazine itself. That would be an interesting place to begin this question of what role has that magazine played in setting certain boundaries around who can speak before evangelicals, but to evangelicals, and what kind of topics are able to be discussed right or debated? It certainly has had that effect. In just the simple fact that it's 20th century American evangelicalism is most important publication far and away, there's nothing, nothing that really can touch it. And that has had an important role.

Randy 44:59

There's an another thread that keeps winding its way through again, to me encouraging that it's nothing new to some depressing that it's nothing new. It's this idea of this deep commitment to biblical inerrancy. It seems like it's kind of the root of all evils in many ways, within evangelicalism, which keeps us from advancing, I want to say and having a more biblical mindset, can you can you just speak to the biblical inerrancy piece of the history of evangelicalism,

Isaac 45:26

the question of the authority of the Bible becomes central to definitions of 20th century evangelical identity. And inerrancy becomes the the most common way of describing what becomes the sometimes official, sometimes unofficial, evangelical position. So you get an organ, another organization, for instance, like the Evangelical Theological Society, for its entire history has had a one line statement of faith where if you can sign it, you are in group official evangelical theologian, and it is inerrancy. If you can affirm inerrancy that is what makes you an evangelical theologian versus all the other kinds of Christian theologians. That's to bring to tie back in one little piece that we didn't talk too much about with with it's why Carl Bart become so problematic among 20th century evangelical theologians, because Bart was by no means any near interest, when it came to the the authority of the Bible. So inerrancy becomes a litmus test, often, if you can affirm inerrancy, you're in, you're a faithful evangelical thinker. Oftentimes, it's in the context of theologians or professors at evangelical colleges or seminaries. The problem I suggest, is what to do about two evangelicals who both affirm inerrancy and then reach dramatically different conclusions about interpretation of an inherent Bible, either, you know, a theological interpretation or the application of a theological tenant that they agree upon, in the political or social realm. Right? You it is a recurrent problem that inerrancy does not solve the problem of interpretation. And often I suggest, because of that, what ends up happening is power struggles, right? Where you have to evangelical groups, some of this did fall out of the book, because a lot of this came in that chapter about the or meaning Wesleyan pipe this tradition versus the reformed Calvinist tradition, because that's a prime example where you get both sides affirming, yes, we affirm the authority of the Bible. But we have dramatically different understandings of how God and salvation work, like really dramatically different understandings of what didn't even have how it even works for one to be saved in the classic evangelical idiom. And that is a tension that doesn't go away, right, this question of what to do about interpretation to some to other chapters, right, the chapter about feminism and gender roles, which is another of those. There are current debates that are happening sometimes among evangelicals about that right now that seem like that has never been argued before in evangelical circles, where you get this divergence, you get convergence on among certain groups view angelical, on 18, you know, a dozen different points. And then a few passages that are have been interpreted to indicate what the Bible has to say about gender roles, divergence over those passages becomes this kind of in group out group thing where you get those who are in power suggesting that if you disagree with their interpretation, you must obviously have given up on inerrancy. And part of the arguments that I don't I don't know if I make this explicitly, but I think this is part of the story that I'm telling is that what happens is you get inerrancy of interpretation, where is the case that those in power set the interpretation? And what is the acceptable interpretation? And then if you challenge them, the move on their part is to say, well, obviously, then you don't affirm the authority of the Bible. Because if you did that, from the authority of the Bible, you had reached the conclusion that I have reached about how to vote or what, you know, what women's role in churches, again, another way to long answer to maybe what was a much simpler question, but I hope that gets at some of what you were hoping for there. It does. It does. Thank

Kyle 49:27

you. Yeah. And our listeners know what we think about inerrancy. And I can go back on their feet and find out if they don't recall, but I would go a step even further and say, yeah, there is no inerrancy without a power struggle, it just is a power struggle like and that's not to say that all an errand tests are consciously struggling for power. That's not true at all. There are many sincere you know, gentle Christians who believe in inerrancy. I know many of them, including some leaders, but like, it is to say that there is no such thing as a doctrine of inerrancy without the attempt to control the meaning of the text until apply it in certain ways to exclude certain groups people and their interpretation of the text. It just doesn't exist without that. It was founded in an attempt to do that. So, yeah, yeah, it's utterly indefensible. In our view, there are very few things we come down hard on on our show. inerrancy that's one of them. That's it's a fascinating

Isaac 50:17

project, the history of inerrancy would be a book I would love to read.

Kyle 50:22

Okay, so let me ask you about, this might be the question I'm most wanted to ask you, actually. So we had a we had an it's kind of nerdy. We had an episode one of our first episodes three years ago, whenever we started the show, about evangelicalism, and in attempting to define it, while recognizing that it's hard to define, we did the standard thing, and we defined it according to the quadrilateral. Bebbington was quoted, mostly identified with David Bebbington, who, interestingly is not American. But for whatever reason, American evangelicalism came to be associated with those four distinctives or whatever you want to call them. And there's a version of that that shows up towards the end of your book. You don't call it that, I don't think but it's basically what it is. And so what do you think about that way of thinking about what evangelicalism is, do you think it's been helpful? Is there any value to it? Do you think it's part of the problem, because defining it that way, automatically excludes, for example, almost all the liberals and a lot of the other people that you talked about in the book. And one of the ways I knew, you know, when I wasn't an evangelical anymore, was when I went back and looked at that and thought not hold any of those anymore.

Randy 51:29

So what do you disagree with that? I think you can hold to bebington quadrilateral. And still like, Be not evangelical.

Kyle 51:36

I totally agree with that. Yes. And so that does complicate it, right? Because you can. Yeah, there are other reasons to not be Evangelical, for sure. So it's not merely belief oriented, but it is a thing that, like, if I don't hold any of those, like what's keeping me here, essentially. So what do you think about that way of framing it?

Isaac 51:54

This one is extremely complicated for a number of reasons. And I'll try to I'll try to simplify an answer here to be brief on this issue, because this is such a fascinating piece of the puzzle. So I wouldn't suggest that the Bebbington quadrilateral as an example of an effort to define evangelicalism is just wrong, we're useless by no means it is naming something and identifying something. I think the difficulty is, and this will bring back full circle and a couple of other questions in topics that we discussed here, one of which is relationship to kind of a new generation of historians looking at evangelicalism versus a previous generation. And one related to your previous suggestion about inerrancy is inherently tied to power and power struggle. So I think that one intervention that I'm hoping the boat makes is around this question of defining evangelicalism and suggesting that at the times when it was painted as about theology, right, when evangelical identity and in group out group stuff was presented by evangelical leaders, powerbrokers, scholars, what have you as identifying these theological tendencies that describe someone or identify someone as evangelical versus not that in those instances, and this is kind of I try, maybe this is a diplomatic way of taking a both and approach that in those instances, when it was putatively about theology, it was at least also sometimes about power? Yeah, right. So without purely painting, everyone, every scholar of evangelicalism, or evangelical gatekeeper is having some sort of nefarious motives that, you know, are not pure in their theological intentions. No, I'm not doing that, or I'm not trying to do that. But to suggest that at times, when it was presented as just pure theology, that questions of identity and power and social location and power struggles and inter evangelical debates were also at play, where it was never just this kind of pure Yes, here is the theological criteria, and if you meet them you are in and here's why. And so this actually ties it back to the book. Because there are folks in every chapter I talk about who would meet that criteria, right would meet the Bebbington quadrilateral or even more specific, even some there are longer lists of even more specific criteria that folks have ventured pollsters like Barna, the Barna Group, for instance, at one point, I think had this like 12 points, you know, there's some kind of long list of beliefs that they suggest these are the evangelical beliefs, or inerrancy, that there are folks in every chapter, I would argue who could meet those criteria and yet for one reason or another, they got marginalized pushed out or written out of the history. And in part that is because part of what then maybe I would suggest is that the something like the Bebbington quadrilateral is not enough to encompass everything that was happening in this thing called evangelicalism in the 20th century US context. There was the sub cultural development thing going on, there was this in group out group movement thing going on, there was power struggles, there was this identity thing going on this kind of trademark, proprietary putting, you know, branding thing going on. And then all of these aspects must be taken into account when we consider what it means to be Evangelical, such that it's not just purely about theology. Maybe that would be a a big kind of 30,000 feet way of trying to answer that question. Yeah,

Randy 55:54

I want to say that I have a feeling that if evangelicalism really oriented itself around that quadrilateral, we wouldn't have nearly as many problems as we do today. But instead we go, evangelicalism has gone outside of that quadrilateral and made it all about whether it's inerrancy, or whiteness, or power, or you know, anti gayness, or all of the stuff. We've made it about everything except for that quadrilateral, I want to say,

Isaac 56:21

black Christianity is a perfect example of that argument in that scholars, even even today, contemporary scholars writing about the history of, of black Christianity in this country, consistently say things like, by any theological definition, black Christians are the most Evangelical, most consistently evangelical tradition of Christianity in this country, and yet are not identified with quote unquote, evangelicals and proper and in fact, don't want to identify with quote unquote, evangelical is improper, and yet meet any of those theological criteria. What's going on there? Right. That's part of the story I'm trying to get at. There's something else going on there. Yep. Yeah, definitely.

Kyle 57:00

So staying on this theme of power struggle just for another minute. So I guess the question is, what do you hope your book is gonna accomplish? But I didn't want to, I don't want to put it quite so pointedly. But like the recognition of the power struggle to define evangelicalism and police its boundaries, that is kind of the focus of the book, as I read it, what do you hope comes out of that like? So one thing that could I could see you hoping come out of it is the a lot of people who are used the word deconstructing, if you want whatever, they feel pushed out by evangelicalism, and they'll see themselves in its history. And they'll see that not only is this not new, it's been going on the whole damn time. And they're lots and lots of people, very smart people who have written copious amounts of really good stuff, who, you know, have made the arguments that I'm trying to make, and they'll feel at home in that. But I also wonder, are there a lot of people like that left? Like, are there a lot of liberals, for example, trying to hold on to some sort of non mainstream version of evangelical? I know, there are a few. But it's also seems like most of them have kind of given up

Isaac 58:01

a quick and short answer. And then a longer a quick and short answer is at least one of the goals that I hope for the book is is just that, that in the writing of history, I think one of the powerful things that history writing can do is show contingency, right, demonstrate that things were not necessarily inevitable, inevitable, or, you know, taking a deterministic view, it was not necessarily the case that evangelicalism would have become what it did. That's one hope that I the book demonstrates for readers for you know, an individual reader. I hope that and part of the reason I centered biography, as a central feature, I wanted to tell some folk stories. If it is the case that someone reads stories here in and feels a little less alone, that would be incredibly gratifying to me, right? This because I also tried to take seriously and honor these folks stories that this is not this is like being excommunicated, pushed out marginalized from one's religious community is a big deal. This is this is like world can be a world shattering thing. And perhaps there are those who are going through something like that currently, who feel like they are the only one. Part of that, I think is a product of what evangelicalism became, in that it became this kind of totalizing culture where it's, at least in certain pockets became like the water that folks swim in. I talked about this on a recent interview somebody about the book where I think it is the case that there are folks who are raised in a religious tradition that might be described as evangelicalism, who somewhere along the way question one piece of the puzzle, and it might end the distinctions here also, I don't want to draw too fast. It might be cool. Cultural more than theological or political more than theological, and I don't think we can so neatly separate all of those things. But I do this is conjecture, I think it's the case that many, many folks who would be going through so called deconstruction right now saw one aspect of something of this culture. And because of how it was presented to them, just as this is Christianity, it becomes like the house of cards that comes tumbling down, where, if one questions, the de facto evangelical orthodoxy on politics, for instance, one is made to believe that one has also questioned one's entire faith. Maybe that would be a little bit conjectural little armchair psychology with some of the you know, the currents inflection point around the deconstruction XV angelical. It seems that this is a thing that is happening right now in a broader kind of folks are connecting with one another about it. So if if in those spaces, folks are able to get a copy, get their hands on the book, I think one of the goals is to demonstrate that this isn't the first time that folks have been forced to ask these hard questions about their faith community, because in certain instances, you know, it wasn't even about theological distinctions or theological choices, right? If you are a black Evangelical, moving in this movement, and you identify with all of the theological criteria, and yet somehow you are constantly being made to feel less than in evangelical spaces, that is not something that you have, you have not chosen to deconstruct, and this is a story that goes back decades.

Randy 1:01:40

It's been forced upon you. Yeah, this is my was my last question slash, you know, compliment is that I'm so grateful for this book. And for books like it, Isaac, that show a way back into the church for people who say can't do evangelicalism anymore. We dropped the faith altogether. And I want to say I love the church. I passionate about the church. And I think Jesus loves the church. And I don't think Jesus cares so much about the evangelical church or any other tradition or denomination. Jesus just cares about the church. And I love that this is perhaps a way back into the church back into following Jesus outside of evangelicalism that this has been going on for 115, maybe more years. So I'm really appreciative of that. Isaac.

Kyle 1:02:22

Yeah. Last question. Do you consider yourself an evangelical? I'm sure you've been asked this numerous.

Isaac 1:02:29

The zillion dollar question, actually, maybe not. So pointedly, I don't I'm trying to recall if anybody if people dance around that a bit in other interviews. I don't worry. They dance around it by asking questions. So like, so what was your what is your background and faith tradition? or what have you? And I don't know that anybody has just i This actually maybe the first time are you evangelical? By the definition of the story that I told in the book, what evangelical means? No, I would not fit to what I believe it means to be evangelical in the contemporary US context. Now, my background is an interesting story that maybe is a podcast discussion for another day. And maybe actually is, could be a whole other book because I there's a story to tell here in that I grew up in the South in Tennessee, in Southern Baptists contexts. And Southern Baptists have a very interesting relationship to this evangelical story. And so the context I grew up in could be described as Evangelical, but that it that language, that identifier wasn't necessarily used, which is a particular kind of thing. It wasn't, you know, we weren't talking those around me in Southern Baptists context. We're not talking, saying things like we are evangelicals, that we are Southern Baptists. And that's an interesting wrinkle on this, which is maybe also a slight bit of a Dodge of the questions.

Kyle 1:03:56

I think that's super common, though, because I was surrounded by Pentecostals for years. And that was the same phenomenon that nobody thought of themselves as Evangelical, but they were those standard metrics.

Isaac 1:04:08

Yes. So maybe that is like no one. In the context growing up. The folks I was around would not have been thinking of themselves in that way, but arguably are by many of the definitional criteria. But along my own personal journey, I parted ways with that particular tradition and denominational upbringing, as have many, so by many, many criteria, especially if you asked folks who are currently those interested in doing some of the gatekeeping around what it means to be Evangelical, there are many things that probably disqualify me, that would be a diplomatic way to put it. Sure.

Randy 1:04:46

Yeah. Well, Dr. Isaac sharp. The book is the other evangelicals the story of liberal black progressive, feminist, and gay Christians in the movement that pushed them out. Thanks for writing this. Thanks for joining us really appreciate your thoughtfulness and care on this matter.

Isaac 1:05:03

Yeah, thanks so much for engaging. I appreciate it awesome

Randy 1:05:20

Thanks for listening to A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar. We hope you're enjoying these conversations. Help us continue to create compelling content and reach a wider audience by supporting us at patreon.com/apastorandaphilosopher, where you can get bonus content, extra perks, and a general feeling of being a good person.

Kyle 1:05:36

Also, please rate and review the show in Apple, Spotify or wherever you listen. These help new people discover the show and we may even read your review in a future episode.

Randy 1:05:44

If anything we said pissed you off or if you just have a question you'd like us to answer, send us an email at pastorandphilosopher@gmail.com.

Kyle 1:05:51

Find us on social media at @PPWBPodcast, and find transcripts and links to all of our episodes at pastorandphilosopher.buzzsprout.com.

Randy 1:06:00

See you next time.

Kyle 1:06:01

Cheers!