A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar

Mixing a cocktail of philosophy, theology, and spirituality.

We're a pastor and a philosopher who have discovered that sometimes pastors need philosophy, and sometimes philosophers need pastors. We tackle topics and interview guests that straddle the divide between our interests.

Who we are:

Randy Knie (Co-Host) - Randy is the founding and Lead Pastor of Brew City Church in Milwaukee, WI. Randy loves his family, the Church, cooking, and the sound of his own voice. He drinks boring pilsners.

Kyle Whitaker (Co-Host) - Kyle is a philosophy PhD and an expert in disagreement and philosophy of religion. Kyle loves his wife, sarcasm, kindness, and making fun of pop psychology. He drinks childish slushy beers.

Elliot Lund (Producer) - Elliot is a recovering fundamentalist. His favorite people are his wife and three boys, and his favorite things are computers and hamburgers. Elliot loves mixing with a variety of ingredients, including rye, compression, EQ, and bitters.

A Pastor and a Philosopher Walk into a Bar

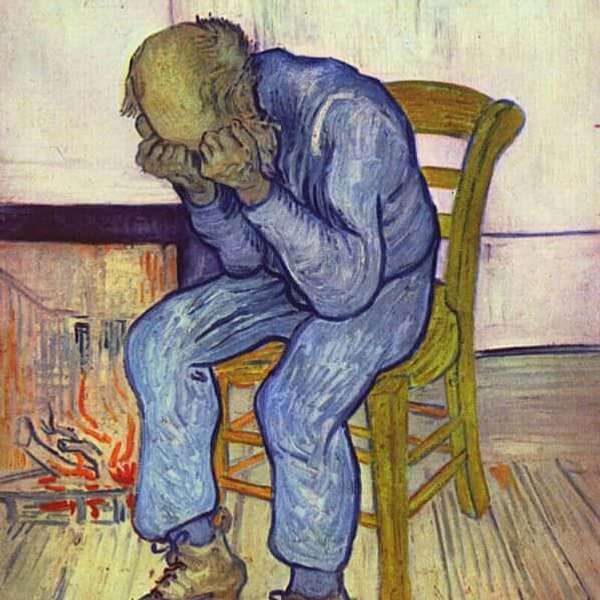

The Problem of Evil (Part 1)

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

How can people who believe in a good God account for the existence of pervasive suffering and evil? This is the oldest and most powerful objection to both belief in God's existence and religious practice, and it has been the subject of philosophical discussion and theological speculation spanning many religious traditions for thousands of years. We've run into it in several previous episodes and each time said we'd eventually focus on it. Here we are. This is part one of a two-part episode introducing the problem and some of the major responses to it (called theodicies), as well as how we think about it personally.

Nothing we say here should be considered definitive or even very confident, and we're certainly not done talking about it. We're barely scratching the surface of an unimaginably vast complex of issues, and we approach it with fear and trembling. We hope that comes through in the discussion.

Due to the subject and the tone of this conversation, these episodes do not include a beverage tasting.

Content note: this conversation includes discussion of evil and suffering and is probably not suitable for children, though we make every effort to avoid explicit extreme examples where possible.

You can find the transcript for this episode here.

=====

Want to support us?

The best way is to subscribe to our Patreon. Annual memberships are available for a 10% discount.

If you'd rather make a one-time donation, you can contribute through our PayPal.

Other important info:

- Rate & review us on Apple & Spotify

- Follow us on social media at @PPWBPodcast

- Watch & comment on YouTube

- Email us at pastorandphilosopher@gmail.com

Cheers!

NOTE: This transcript was auto-generated by an artificial intelligence and has not been reviewed by a human. Please forgive and disregard any inaccuracies, misattributions, or misspellings.

Randy 00:06

I'm Randy, the pastor half of the podcast and my friend Kyle is a philosopher. This podcast host conversations at the intersection of philosophy, theology and spirituality.

Kyle 00:15

We also invite experts to join us making public a space that we've often enjoyed off air around the proverbial table with a good drink in the back corner of a dark pub.

Randy 00:24

Thanks for joining us, and welcome to a pastor and philosopher walk into a bar there's a number of things about our spirituality that we really don't think about much as Christians in particular, in particularly as American Protestant Christians, there's a number of things that are problematic about what we do or don't believe about what we believe, but we don't really think through. And when we say things, the problem emerges. And one of those things is the problem of evil. What you philosophers Kyle would call theodicy, how to explain the problem of evil in light of the fact that we have a God who is omnipotence, omnipresence, all knowing whatever that is, omniscient. All those things, if God can do whatever God wants to do, why is there still terrible, awful atrocities and evil in this world? That's a problem.

Kyle 01:22

Yeah, it's really the problem. If you're, if you're a religious person of any kind, really, this is not unique to Christianity. It's something everybody who thinks there's a higher power that is basically good and has to confront. And it's easy to go your whole religious life without confronting it. Or you just kind of, you know, press it down, and unless you yourself, encounter some great evil,

Randy 01:46

or you just suppress it with some platitudes, like God's in control, or, you know, God wanted another angel, or whatever, Bs answer we give to really terrible stuff happening to really good people.

Kyle 02:00

Yeah. But we've we've come across this a few times in previous episodes. And every time it's come up, we've said, We don't want to talk about that yet. And we've kicked the can down the road a little bit, but we'll get to it. And I guess now we're getting

Randy 02:13

for better for worse or better.

Kyle 02:14

Yeah, I'm not excited about this episode. I've I've never not wanted to talk about something more, I think, is there and I had to like drag myself to create an outline for

Elliot 02:22

so total outsider here. Why has it taken so long to get to this? Because it does seem like it's at the same time as it gets really heavy. And there's a lot of philosophical thought about it. It's kind of like the most basic objection to God that there is like, that's, you know, because because somebody I love got cancer, God can't be good. I hate God. God, like or God can't be real. Like that's, it's the most classical objection. There is right? Yeah. So why why did it take so long to get to it? Because it's difficult.

Kyle 02:53

That's part of it. I can only speak for me, for me, it's to twofold it's one psychologically, just taxing and stressful to think about. It's not just a philosophical problem, right? It's, it's something that goes to the basis of what it means to be a human being. And tinge is every emotional experience I've ever had in my life, including the good ones, there's always this behind it. It's, it's the kind of problem that, like any real philosophical problem, I think, taking it seriously should change your life. And it has changed my life in a significant way. Like, I don't think about God or my faith, or even my relationships the same way as I did before I seriously looked into this problem. And I was also flipping about it as a college student, which I deeply regret before learning better, and actually experiencing some real suffering. So part of it is it's just, it's just psychologically stressful. And I don't like that I taught it every semester. Because it's, it's a classical philosophical topic, as we'll see. And every time it was a chore to drag myself in there, had to fight back tears getting through certain parts of the lecture, wasn't always successful, just rough and all the other sincere religious people I know, who also taught it regularly had similar experiences. And some of the reading on it is just just awful horrendous to get through. And I can recommend some if people are interested. But you know, the best work on this is the stuff that takes it super seriously and honestly, and deals with real instances of evil and some of those things are just almost impossible to think about. So that's part of it. The other part of it for me is that I feel really inadequate, like I don't, as you'll see, I don't know of a solution. And that's a problem. It's, you know, inadequate in two ways. Like I can't solve it on one hand, but also inadequate and like the only tools I have to approach it seemed like the wrong tools, which are analytical, philosophical tools. And that Yeah, I think there's a place for that. I'm gonna do that. In this episode. I'm gonna explain why I think that is important to do but at the same time, I know that it's not sufficient, it's not going to solve anything. And it's, it's exactly the wrong thing you should do. If anyone is actually suffering, you know, giving someone a rational argument as a justification, or you know, some, it's no help at all, it's not gonna help someone dealing with real suffering. Yeah, no

Randy 05:19

one in their suffering needs a over spiritualize corny platitude to make them feel better. It doesn't help anything. As a matter of fact, it hurts things, and no one needs in the moment of their suffering, a philosophical, you know, idea of why they're going through what they're going through and why it might be better. All they need is for you to sit with them. They don't need explanations. They don't need platitudes. They don't need cheesy sayings. They don't need Bible verses, literally. They just need you, you to be with them. You do mourn with them, you'd agree with them. So there's there's one thing that's the pastoral side, but the philosophical side, the theological side, I think part of why it is daunting, and why we don't really love talking about it is because if there is no answer that leaves you feeling, oh, there it is, you know, I mean, I've got my ideas, but most of them leave you empty. So this is we're getting every all our listeners really excited to listen, because this is gonna be really rosy and cheery. But here we go.

Kyle 06:20

Yeah, and, you know, we've had episodes in the past where we gave disclaimers, and said, you know, this is gonna be trying. And if you're in a psychological place right now, where you don't necessarily need this, feel free to skip it, this is definitely one of those. But this is for the person who, when you're in the mental space, where you have the energy, and you have the strength, and you feel like this is something that you need to wrestle with, hopefully, this will be a resource for you to think a little bit more rationally about some of the not some of the the biggest problems that have to do confront religious belief, and theism itself. And so it's a resource. It's an important topic. I want it to be out there. Yep, let's get through.

Elliot 07:02

Yeah, so maybe, can I ask if I'm somebody who now at the beginning of this episode is thinking, Yeah, this is my primary objection to God, either to his existence or to his worth in my life. And I would love to actually get to, like think through this to a point where I'm able to overcome that challenge and embrace God or faith or something. Like, should I anticipate should I hope that at the end of this conversation, I at least have something like it? Will there be any progress made? That I can look forward to? I think, so.

Kyle 07:39

We'll see how it goes.

Randy 07:43

If nothing else, I think you'll have a model for how to think about it, and how to go about that in kind of all the ways you'll

Kyle 07:51

have lots of examples of ways that really thoughtful, careful, people have tried to deal with it. And some might find that helpful and hopeful and might identify with one of them and a helpful way. I think that's dependent on the person.

Elliot 08:05

Sounds worth the time.

Randy 08:06

Yeah, no, I mean, if if you're looking for just a verbatim empirical answer, you're not going to find it here. And you're also not going to find it pretty much anywhere. Right? Yeah. You've done a lot of philosophical reading. Kyle, have you found any adequate answers to the problem? People

Kyle 08:20

know? Well, none that satisfy me, right. And in fact, I think that's kind of commonplace amongst philosophers who specialize in this problem. Most of them will say, even ones who have like, carved out a position for themselves that they're kind of known for, I think most of them will, if being honest, will say nobody's solved this, right, including the religious ones, who are the ones who probably think the deepest about it, because it impacts their faith. I don't know any serious philosopher who specialized in this that thinks there's a clear cut? Yeah, answer that solves all the issues. Yeah. But there's like a family, whole constellation of attempts that share some really interesting similarities. And I want to talk about those.

Randy 08:59

Yeah. And I think there's all sorts of of space to say, this is the problem, we should talk about it, we shouldn't ignore it. We might not get to any real concrete, black and white answers. We might have have to embrace the mystery. But also we're going to deal honestly, with our faith.

Kyle 09:16

Yes, yeah. That's exactly what we're doing here. We're taking the problem seriously. So a few preliminary remarks, obvious content warning, we're talking about serious stuff. So if you need to check out checkout. I will say this, though, there's a really annoying tendency amongst, I've noticed that amongst philosophers, I think it's broader than that. But in particular, philosophers, when they talk about this problem, they go immediately to the worst, most graphic examples of evil to illustrate their case, with usually no content warnings, we're not going to do that. So if you're worried about that, that's not going to happen. I'm going to use examples. That might be difficult to think about, but I'm going to try to avoid using examples at all if I can, and they're not going to be you know, the things that probably spring into your mind, like anybody sufficiently imaginative can imagine up their own terrible cases, we don't need to do that for you. So we're not going to do that. But we are going to take this really seriously, it's going to be heavy. And so if you need to check out no judgement. Another disclaimer is that there's a bunch of ways of approaching this problem. And none of them are authoritative. There's no such thing as an authoritative philosophical method at all. And that includes on this topic, but minimally, most philosophical approaches to this involve logically rigorous argumentation. And so when I said I feel inadequate with the tools that I have, it's part of what I mean, like what philosophy uniquely brings to this is a kind of rigor of thinking through reasons for and against certain kinds of claims. And so the problem of evil, as it has been proposed in the history of philosophy is a philosophical problem in the sense that it's an argument. And there's a conclusion that it's trying to refute, and whether or not it has done so successfully forms a huge part of the history of Western philosophy. So that's how we're gonna approach it, because that's just what the tools of my discipline bring to bear. And I think it's valuable to do that. But as I said before, it's not sufficient. So you're gonna get one kind of take here, one kind of approach, and it does what it does, and it doesn't do what it doesn't do.

Randy 11:20

Yeah. And this is one of those episodes where it's philosophy, heavy Kyle's driving this outline, in this conversation, and also, but also, pastors have a place in this conversation, because we're the ones who deal with people in real time. We're the ones who mostly people call when the crap of their life hits the fan. And I think that perspective matters as well. And I think similar to what Sharon yet have said, about Sameer, who's a theologian. Share it, I loved it when he said, My brother works for me, like the theology works for the pastor's because I get to disseminate that and translate it into for the Congregation for the people of God. And this is where I kind of feel like Kyle works for me like, exactly a second, too, and bring all that philosophical background and insight, so that I can go to people and so that we can go to people in their pain, and bring something of God something of truth, something of meaning and goodness to them in their pain.

Kyle 12:16

Yeah, I feel that deeply. And I really do think I'm happy to play that role. In a way, this is the most fitting topic for our thing we have going on here, right? It's it's the most obviously relevant to both spheres. And I'm happy at the end of it to like, lay down what I have and be like, I hope that's useful. It's not I'm really sorry. Yeah.

Randy 12:38

So without further ado, let's get into this. Let's get into it.

Kyle 12:56

So real, real quick background, about the relationship between God and morality. So we've talked about having a little series of episodes that we pick up every now and then maybe when there's a lull or something between interviews, maybe we call it the philosophy 101 series or something like that. I don't know, you could consider this like part one of that if we want. But this would be like, if you were to take my intro philosophy class, these are the sorts of things we would talk about. And one of the things we've talked about having a little mini series of episodes about is ethics. And so I want to eventually have an entire episode just about God and morality, because it's really interesting christian ethics versus secular. And we'll have a Christian ethicist on CNN. David gushy. Yeah. Oh, yes, excellent. So definitely, we're going to talk more about this. So this is like a very cursory, 30,000 foot view of, of this topic, gotten morality just because it's kind of important background information. So to raise what's called the problem of evil at all, to say that there's there's suffering in the world, and it constitutes some kind of problem for theism is to already to see a conflict between God and evil is to make moral judgments about the state of the world, and to make moral judgments about God. And that implies a few things that might not be immediately obvious one, it implies that God can be the subject of moral criticism, which is kind of controversial among certain theological systems. It implies, for example, that a really famous and really old and really influential Christian theory of ethics is false. And that theory is called variously Divine Command Theory, or theological volunteerism, whatever you wanna call it. It's this view that morality is rooted in God's nature, or in God's will more specifically, so that whatever God commands is what is good or right. Those principles just are constituted by God's commands are God's will. And if that's the case, then anything God commands is good. And anything God forbids is bad. And that's just the meaning of moral terms. That's called Divine Command Theory. if it makes any sense at all, to put God under a kind of moral microscope, then that view is automatically wrongheaded. We're automatically like disregarding an enormous swath of theological history there. So I just want to make that plain to raise this problem is to is to kind of take a stand on that view,

Randy 15:21

which I feel like too few people with who either hold that view, or who even just tried to broach this topic. Don't see a difference between God. Yeah, the divine life, in our concept of God. Because if we're talking about our concept of God, then we should really hold that under the microscope and apply this conversation to it. When you talk about God, all of morality flows from God and all the stuff. I would agree with that, but we don't have a clear picture. You know, we don't have this. Here's the Bible, and it's perfect and pure in there, all our questions are answered. And it The Bible doesn't work like that.

Kyle 15:58

No, nothing in theology works like that. Yeah, so we're definitely going to have a whole other episode talking about this. I just wanted to make that point at the beginning that even raising the question implies some interesting things theologically. Another thing that might imply this isn't entailed, but I think it's implied is that if it's possible to mount a moral critique of God, you might need to do that using non theological sources, or non religious sources, which raises the possibility that a lot of Christian apologists and Christian ethicists don't like, which is that you could ground an ethic in something else, that secular ethics might be better, or at least just as good. And that is, in fact, my own view, which I want to talk about at a later date. And then another thing we're implying here by raising the problem is that the world could be better than it is. And maybe that's obvious. But a lot of theologians and philosophers have denied that. So one type of theodicy, which we'll talk about later, is that that's not the case that this is the best world. And that's a way to get out of the problem, right? You say what was the best God could have done? I'm not satisfied by that at all, I think it's very obvious that it could could be better. So if you agree that suffering is a problem, you're taking that view, and then one more piece of background information. And that is about how intuitions work in this conversation. They're unavoidable in my view, intuitions, and then you can think of intuitions as kind of like judgments about states of affairs in the world, that are kind of pre theoretical not not really fleshed out, not really super deeply considered, something strikes you as being true about this. And we all have them. And interestingly, they differ. And they differ in sometimes predictable ways. And there's a whole, you know, field of philosophy that's interested in how they differ, and whether or not we can trust them. But when we talk about things like take instance of suffering, X, some people will look at x and immediately feel that's obviously wrong. Other people might look at us and feel it's wrong in some situations, and not others, others might think it's just good. And so when philosophers are fishing for examples, to talk about evil, this is one of the reasons they often go to extremes, because they want everyone's intuition to be really strong. And so they'll use cases like Hitler, you know, because everybody has a really strong intuition that we're all really sure about. And intuitions are the thing that we're trying to explain when we do ethics. That's one of the things we're trying to explain. So I'm not apologizing that I'm going to be relying on intuitions here, I just want to note it because it's unavoidable in my view, that would make some philosophers mad, by the way, what I just said. So just note that, okay, the problem, what is it? So when I, when I broach this problem with my students, we've already had a whole section prior to this, about what God means. Which is a whole nother thing that would take a long time to go through. But one of the things I tell them is that try to and considering this problem, if it's possible, I know it's hard, but try to take all the things you have convictions about from your religious practices or your faith, and try to bracket those just for the purposes of the conversation. And instead of thinking of God as a person, or as a name of a being that you've had interactions with, and that you think, you know, think of God as a title, a title that may or may not be held by something, and what would be included in that title. This is a way of trying to think about the problem, rationally trying to put a little bit of emotional distance between you and the issue. And again, I hesitate to even say that, but it's important for doing philosophical thinking clearly in most cases. And so if we think of God as a title, rather than a name, and we ask, what would it take to have that there are certain attributes or characteristics or features that go along with the title or the idea of what a god would be? And most of these attributes are that there's a set Have them that have been very persuasive to most of the people who have thought about it, at least in the West, but not just in the West. So you've heard of things like the Omni attributes, right, omnipotence, omniscience, Omni benevolence, Omni temporality, um, many presence all those omnis just means that anything that held the title of God would have these certain features to their maximal degree, because that's just kind of what we mean by God. Right, as Anselm put it back in the 12th century, or whatever. God is the greatest thing, the greatest conceivable thing, if you could think of something greater than the first thing you thought of wasn't God, you need God has all the attributes that make a thing? Great. That's the title. And then the question is, is there anything like that. And so before my students ever get to the problem of evil, we've we've talked extensively about that, we've talked extensively about each of those attributes, what they are, what they entail, what they don't entail. And we have a really clear idea of what God is, I'm not going to bore you with all that going into this, but just try to separate if you can, your religious convictions about God from the kinds of traits that you think a God must have? Sure. And the important traits that we're going to be focused on here are three things, one, knowledge, to power, and three, goodness, that third one's really important. The combination of those three things with the fourth thing, which is the fact of suffering, creates the problem of evil. Yes, so you can think of it as an inconsistent set of claims, there is a being who has the knowledge to eradicate evil, that being also has the power to eradicate evil, and that being wants to eradicate evil. In other words, that being is good. And number four, evil exists, those four things are unconstrained, or at least they seem inconsistent on the face. And so the challenge to the theist is to explain how those things can possibly be consistent. That is, in essence, the oldest form of the problem of evil. We'll talk more about that specific forum in a few moments. Another part of the setup, that's important to note, I think, is that this is an incredibly persuasive argument to a lot of people against theism, so much so that it's, it's really, I don't think it's an exaggeration to say it's almost the only argument against theism that gets any real focus. And one reason for that is that a lot of people just think it's enough. It's sufficient. It's decisive all by itself. It has various versions, we can talk about some of those versions. There's another related problem called the problem of hiddenness, which is, why does God seem so hidden? Why can't more people find their way to belief in God, but I think that's really kind of a version of the problem of evil because it's a kind of suffering, to want to be in relationship with God and find that blocked in some way. So there's lots of versions of it. But there aren't really any other objections to theism. They get a lot of philosophical attention. This is yet and a lot of philosophers think it's enough. So that's just worth noting. Okay, so there's two primary vert, there's more than two, but I'm going to talk about two versions of the problem of evil. The one I just gave you about foreign consistent sets of claims, that goes all the way back to Greek philosophy. So Epicurus gave a really famous version of that was more or less what I the way I put it, if there's a being who knows how to stop evil, can't stop evil wants to stop evil, there shouldn't be any evil, but we look around and there's a whole lot of evil. So that's called the logical problem of evil because it says, there's a logical contradiction. There's an inconsistency between two facts. God exists, evil exist, they shouldn't, they shouldn't exist. And so the logical problem of evil is very strong. It says that God can't exist. That's the conclusion. If those four claims can't be true, simultaneously, logically speaking, meaning it's impossible there is as the philosophers like, say, there's no possible world where God exists, and evil exists just isn't a thing. And that was really influential. You had David Hume pushing something like that. I mean, it was convincing to a lot of philosophers for a long time. In the last 6070 years, it's been a lot less influential. I don't want to say it's been solved, but there's been a lot of philosophical work on it that have kind of ended discussion about it, and mostly, and attention has shifted to a different version of the problem. And just real crudely, one way to see why that discussion ended, is to think of any theodicy that's really common and has convinced a lot of people because all you really need to show that it's possible, logically possible for God to exist alongside evil is some relatively convincing reason why God might have allowed evil. And that's what the Odyssey is aren't right freewill is a great example. And so we tell stories like the story of Adam and Eve in the garden, that suggests that humans had some kind of role to play with respect to the kind of being God wanted them to be, which involved agency agency. And so now suddenly, we have a reason why an omnipotent, omniscient, Omni benevolent God might have allowed the existence of evil. And the reason was some greater good, yeah, we're gonna get to that later. And so that you may or may not find that convincing, but it kind of does undermine that logical problem, right? Because the logical problem has has gone out on a limb and made a really strong claim. This is impossible. Yeah, all you got to do to overcome that and show that it's possible. And so philosophers kind of got bored with that. They moved on to something else. And the thing they moved on to has various names, I'm going to call it the evidential problem of evil. And it's called that because it's kind of probabilistic. And its conclusion is not about what's possible. Its conclusion is about what we have good evidence to believe, what is reasonable? What is probable, and it argues that, while it may be possible for God to exist alongside evil, the existence and the amount and the intensity and the variety of evil that we observe in the world, makes it incredibly unlikely that a good omniscient, omnipotent God

Randy 26:26

could exist, which seems very similar to the logical argument to me. Yeah,

Kyle 26:30

but with a crucial difference. It's not saying God can't exist. It's saying God almost certainly does not. You don't have good evidence that God exists. And in fact, you have overwhelming evidence that God does not exist. That's the conclusion. And that's a lot harder to combat.

Randy 26:46

But that's just specifically if we're talking about the problem of evil. Yes. Because I think that that conversation is much broader than just the problem of evil. existence itself. Could be I would think, philosophically, certainly theologically, some sort of evidence that God exists.

Kyle 27:06

Oh, okay. Yeah. So you're thinking like a cosmological argument is causing

Randy 27:11

logical or consciousness is, is kind of existing evidence that perhaps there's something greater than us? Yeah, like, you could go down the line with some of these things.

Kyle 27:22

Yeah. That old canard? Why is there something rather than nothing? A lot of serious philosophers have thought that implies some kind of theism? Yes. Okay. So I would, I would view that as, interestingly, when I, when we do this in class, we've also previously had a unit on God's existence. And we've gone through all these arguments, the cosmological arguments, teleological argument, the moral argument, a bunch of others. And so we have like this weight of evidence on the side of theism coming from all these different strains of evidence, like, for example, that anything exists at all that might be a kind of evidence or that things developed from a finite point in the past, that might be a form of evidence, and to some started, there was a cause that anything has an explanation at all, if the whole ball of wax has an explanation, what could possibly explain it, it can't be part of or morals or general. Exactly, you know, maybe morality itself points to a law of some kind. And if there's a law, maybe there needs to be someone who source of it. Yeah, exactly. So. So we've already gone through in class, you know, all those those reasons are for rewinding. But no, that's fine. This is a good point. And so what I like to tell the students is, look, we just went through, you know, 12, or whatever it is arguments for God's existence, theists have given a bunch of them. And then on the other side of the scales, we have one argument, which is the problem of evil. And I don't have hard data on this. I don't know like where the majority opinion falls. But it is not clear to me that the scales tip in the direction of theism. If you're just talking about general opinion of specialists in this field, that one might be enough to, to counterbalance all. So that's kind of how I think about it. The problem of evil doesn't undercut those kinds of evidence, they're still real kinds of evidence, it just gives you another kind of evidence that is maybe weightier, or maybe a little more sure. Because when we're talking about things like you know, the beginning of the universe, our intuitions about that get pretty thin. Mine do anyway, I don't have real clear intuitions about how the Big Bang and God relate to each other. I have opinions, but at the end of the day, they're based on something pretty flimsy that I barely understand. But I have real strong intuitions about suffering, and about the goodness of God. And so that tends to be experienced as a little more weighty or authoritative. Yes, yes. That's a good word for it. Yes. So the evidential problem, let me give you an example of it from the philosophical literature. And this is hopefully a palatable example for most people, but it's still a little bit difficult, especially if you're like, really sensitive about animal suffering. So fair warning. So a guy named Bill row was an atheistic philosopher of religion, call himself a Friendly Atheist, because he tried really hard and

Randy 30:07

passionate, conservativism kind of guy.

Kyle 30:09

Yeah. But he did really try hard to understand theism. And the arguments from its strongest proponents and took it really seriously and was never dismissive or condescending, or anything like that, which is fairly unusual for the atheist in recent years. He was really good at it. And so he mounted a version of the evidential problem of evil, and he used an example that I always use in class, and that's involves a deer. Okay, a fawn like Bambi, like, you gotta go here. I know, I gave you fair warning. And so he says, imagine a fawn gets separated from its mother. And, you know, freak, lightning strike, starts a brush fire, and familiar to all of us these days, you suddenly have a raging wildfire. And Bambi gets caught up in the wildfire. But maybe it's just on the edge of the wildfire. So Bambi is not immediately killed. Bambi is severely burned. And it takes, let's say, days for Bambi to die in

Randy 31:12

agony, like calling this dear band.

Kyle 31:16

Yeah, I know, this sounds a little flippant, but I actually do think that this is a serious problem. And so Bill row says, that kind of suffering clearly happens. Right? Yeah, it's probably happening somewhere. Now some version of that is happening somewhere. Now with all the wild fires that are raging, and many, many places in the world. Yes. And here's the thing about that kind of suffering. No one ever knows about it. No one finds out. Nothing good comes from it. At least it's very hard to see what could could come from it, right? Because there isn't any entity that could learn from it. There isn't any. It doesn't ever get better for Bambi it doesn't ever get better for baby's parents. It doesn't ever get better for the environmentalists who care about that problem in general, but don't have any actual awareness of that specific case. It's just real hard to locate any reason for that anything that could seem like if I was a good person who had power over the situation, I would still let that happen to bring about in X. What could X possibly be? It's hard to say. And the ease of coming up with examples like that should give you pause, that the world is full of instances of suffering that don't seem to have any purpose at all. And Bill row called them gratuitous as the word he used and gratuitous just means unnecessarily bad, or arbitrary. reasonless purposeless. And while it may be the case that we're going to see this and when talk about more of the theodicy is in a minute, it may be the case that God might have some reasons for allowing some suffering, right? It's easy to think of examples of hardship, that make one more resilient, or that build your character, right. In class, I like to use example of like breakups. We all had difficult breakups as adolescents. And at least in my case, I think they made me better, right? They made me more mature, or we all make stupid decisions, and we suffer the consequences, and we learn from them. And we become better people such that we can look back at them and say, I'm actually glad that happened. It was awful. In the moment, it was the worst thing that ever happened to me. But I'd be a worse person if it didn't happen. So clearly, God could make a really good world and put some suffering in it. Maybe even great suffering, that at the time, this experience seems like the worst thing ever. But what God can't do is have arbitrary suffering, suffering that leads to no purpose leads to nothing good. There can't be gratuitous suffering. And so Belrose said, but there is it's everywhere. It's not hard to think of examples of it, including examples involving humans and innocent humans. And so what what is the evidential, you know, situation with respect to God's existence? How likely is it that a good God with all the power and all the knowledge to prevent gratuitous suffering exists when we see so much of it? So that's the evidential problem. His his argument was we have tons of evidence, just look around that the Christian God, for example, can't exist. That's hard. That's hard to deal with. And it works for lots of different types of evil. Now just gave you an example of natural evil. Something nobody is nobody's fault, because like one common theodicy is freewill which we just mentioned. And that says evil is the result of human decisions. God wanted something really good. And that good thing was a relationship with humans. And in order to have a real relationship with somebody, it's got to be two ways, which means there has to be a choice. On the other end, God couldn't have just made robots. So God gave us a will. And that It carries with it a kind of risk. This is how the freewill theodicy goes. And so God took that risk knowing that the end was going to be so great that it would justify whatever might have gone wrong and giving us that gift. And so we can explain a lot of the evil in the world by humans abusing that gift. That's the most probably the most popular theological response to evil Augustine, for example. But it doesn't touch Bambi. Right? Because nobody chose that. It was just a bolt of lightning,

Randy 35:28

except for, you know, the belief that Adams curse, you know, goes into nature. And yeah, Apostle Paul says in Romans eight that all of Christian is, you know, crying in childbirth longing for the sons of God to be revealed. I'm stumbling over my words, because I wasn't thinking of it. But I think there's a way for us to understand that in a in a Christian way that actually doesn't make that the like, Bambi that isn't the unsolvable problem.

Kyle 35:56

Yes. But we're gonna see this with every theodicy we're going to talk about is my refrain at the end of it is going to be but what is the evidence? Tell us? What do we actually have good reason to believe? And personally, speaking, for me, it's very difficult for me to see any convincing case that something like that is true. In what way that would justify a particular instance of suffering that I'm looking at right now. And it would still remain the case that surely God could have thought of a better way to do this. Right? Couldn't we have had a world where there's like three last year the dying wildfires, that'd be better. It's just obnoxiously easy to think of states of affairs that would be better than this one. So I don't find solutions like that convincing but well, we'll give them their fair shake in a minute.

Randy 36:43

Yep.

Elliot 36:52

Friends before we continue, we want to think story Hill, BK C for their support. Story Hill, BK sees a full menu restaurant and their food is seriously some of the best in Milwaukee. On top of that story, Hill PKC is a full service liquor store featuring growlers of tap available to go spirits, especially whiskies and bourbons thoughtfully curated regional craft beers and 375, selections of wine. Visit story, Hill pkc.com For menu and more info. If you're in Milwaukee, you'll thank yourself for visiting story, hope PKC. And if you're not remember to support local, one more time that story Hill pkc.com.

Kyle 37:37

So this is why when we talk to Keith de rose, if you haven't heard that episode, go back and check it out. Probably the most focus we've had on the problem of evil before this. He called the problem of evil a killer problem. Yes. He's somebody who specializes in it. And what he meant was, if you don't have an answer to this, you should not be a Christian. Yes. You shouldn't be a theist of any kind. If you don't at least think that there's a possible answer to this, or that you're, you know, you have some kind of hope for resolution to this. It just doesn't make a lot of rational sense to continue doing. Yeah, it's a killer. I would agree with that. It stops the faith. Yeah. And I think we're, we're kind of both in agreement with him about that. So for that reason, some kind of response seems required. And those responses are called theodicy. So I don't know why they're called that. But it's an old term that philosophers go to the etymology of the word. So there's a bunch of these, and I've got a list here we can talk about, I'm curious from you, maybe before I go through the list, in your experience as a pastor, what kinds of theocracies do you typically see, use the most? But is there like a way that pastors tend to approach explaining suffering to their congregations that you think is, I don't know, especially good, or maybe especially bad, especially common.

Randy 39:01

I don't like this because I have pastor friends who listen, and I don't want any of them to feel like I'm talking about them. But you guys tell me if I'm wrong, but I feel like, first of all, there's not many pestle attempts to solve the problem of evil. We kind of just assume that God is good, and we ignore all the all the ugliness of the world. And then we can I mean, there's a whole range, right? I mean, Pat Robertson said that Haiti, the earthquake in Haiti happened. I don't know when that was 2011 or something like that. Because of all the Voodoo that happened. Or, you know, pastors have said that Hurricane Katrina happened because of all the ungodliness happening in New Orleans, the tornado that touchdown at the ELCA convention when they were talking about whether ordain gay clergy happened because of the you know, gates. You can go on and on and pastors and church leaders have explained away natural disasters in particular but atrocities and evil and disaster on In the human sin, right, so that's one way that pastors and faith leaders have have tried to solve this problem is just like it's, it's our fault. It's your fault. It's those centers fault. It's usually not our fault. It's their fault. That's one way. Another one is just this kind of, and I don't know how much we think through the stuff. But what I've mentioned at the beginning of the our time, which is just the sovereignty of God, you know, God is in control. God is sovereign, and it's our job to trust him. I think that's probably the most common one, even in non Calvinistic, non reformed traditions. We're almost not we many, many churches are Christians that even don't claim to be reformed. Functionally, conversationally, come across as reformed, because they will say those things. Well, I don't know why that happened. But God's in control. I trust God

Elliot 40:50

that you just wrap it all up in the it's the eternal perspective, right? Sure. Like you've got, we live in a fallen world. And so you just grin and bear it. And like later on, it's all gonna be worth it. You kind of just gloss over this part that's less significant than whatever is to come. Yeah. Which is kind

Randy 41:04

of what I do. When I'm gonna explain what I believe in my like, layman's, the theodicy, it is like, there's something better to come or that God's gonna make all things right at the end. I trust that. And I believe that, and I think there's a place for that. I don't think that's inherently bad. But it's not like evidential, like you're you keep on hitting it. And I'm going to tell you, no matter how many times you say that, that's not the end of the conversation for me.

Kyle 41:31

Yeah, I don't want it to be.

Elliot 41:34

What would evidence of the fall look like if, if not the world around us, which is obviously broken? Like, I don't know how, how else you could pursue that track?

Kyle 41:45

Yeah. So the the evidence that I'm mostly concerned with here is, is there sufficient evidence for any of these the Odysseys that we're about to go through to counterbalance the vast, pervasive evidence of suffering around us? And its inconsistency with the good God? That's gonna be the question, do we have enough to kind of outweigh or to give us good reason to hope that maybe we're just mistaken about this, because that's really what we have to conclude, if we're going to continue being religious, in the face of the problem of evil, we got to just be mistaken in some way about how things seem to us. That's part of the power problem.

Elliot 42:20

But isn't the idea that like the world is broken? Like we all acknowledge that there is suffering, Bambi suffers a long, painful death, but God is putting all of the pieces back together. It's just not Yes. It's not together again, yet.

Randy 42:35

Yes. And that's, that's the part of this conversation that might be missing in philosophical circles is, I'm a person of faith, because I choose to be a person of faith rather than not. I think that's a better way to live. And in many ways, I'm a person of faith, because I choose to be a person who is fueled by hope for what could be rather than just what is an accepting that, and that's not evidential base. That's, you know, it's a whole nother conversation. But I think it's important to hold on to when we're having these conversations. Yes,

Kyle 43:06

that's fair. And I think we've talked before about the difference between being an ear rationalist, and a kind of, I don't know someone who thinks that faith happens when reason has run its course when we talked about Kierkegaard we talked about this, because I can be somebody who thinks that the evidence is ultimately indecisive. And in fact, that is my view about evil, just laying my cards on the table. But in a case like that, I think it's totally reasonable to then pick an option that has some other benefit outside of epistemic benefits. Yes. In other words, it's not superior in terms of what any person can know. And it's not superior evidentially, but it does have some psychological benefits, maybe it has some emotional benefits and might be good for my overall mental health. It might be good communally. It might help me to build a really healthy community that might be better for the world. And yes, exactly. It might help. Yes, exactly. So that's reasonable. That's different from being an ear rationalists, which is to work against the evidence. And what we've got here. And the evidential form of the problem of evil is a strong challenge to for the theist or the religious person, to show how they're not being irrational and continuing to be religious, because they're surrounded by evidence that God shouldn't exist. And so what we have to give is something that gets us back, not necessarily the tips, the scales back and towards the direction of theism being the reasonable option, but just not being unreasonable. Like we're just trying to reach an equilibrium here. Yes. Yeah. So I love asking people how they deal with the problem after it's been formulated. I do this my students, because you always, you know, in a class full of 20 students, you get most of the historical theocracies they just come out yep. Of your intuitions, because they're just the most obvious ways of trying to deal with the problem. You always get free will. You always get some version Then of things are going to be better eventually, afterlife Yeah, so much better, that it will in some way account for and justify how bad they were before. So I like to call this the tapestry theodicy, because I've heard it used in that kind of metaphor of God as weaving a grand tapestry of life. And, you know, if you look at a beautiful tapestry, I show my students a picture of a tapestry from the front side, and then another picture, the same tapestry from the backside, and the front side is beautiful. And the backside is marred and ugly, and has loose strands and everything. And so the problem, of course, is that we don't see the whole picture, we've got a very narrow focus. And if we could see things from God's perspective, all the bits that seem terrible would have their place. And of course, if you didn't have contrast, you couldn't have a beautiful work of art. And so what God sees is the whole and how each instance of evil plays a part in that episode over right but you know, I say this. I try not to be flippant about it, but like I like that I don't find at all I don't find anything convincing about it. I think you have to be remarkably privileged as a matter of fact, to find that satisfying all by itself. And yet something I'm not kidding here, some of the greatest minds who have ever lived, people like Gottfried Leibniz, who discovered calculus, and was just intimidatingly brilliant. Took that view. And then Voltaire made endless fun of him about it.

Randy 46:24

It's hard to like know, history and take that view. Yeah. And

Kyle 46:27

yet these people did. They weren't dumb, they, you know, read extremely widely and yet, but it's a fun, beautiful metaphor. It is yes. And in certain contexts, it can be really persuasive. I've heard it delivered in various forms in really persuasive ways by good orators who had the right kind of context and audience and the music was playing just right. And it can seem really compelling. So that's one kind of theory. That's one kind of see artists give us some others. Another is freewill, which we've talked about. We don't have to say much more about that one. But it has obvious limits, right? Because there's only so much evil it can account for unless you're willing to say things that I think stretch the evidence to the breaking point. So for example, Greg Boyd, has a version of the freewill theodicy that he calls a warfare theodicy. And he solves the problem of natural evil by saying it is still about free will. It's just demons. A spiritual warfare. Yeah, it's their free will,

Randy 47:20

which is a very, like, that messed up nature, ancient way of looking at it. Yeah.

Kyle 47:25

Or we have some kind of real creative agency and the choices we make impact nature in ways that we haven't quite taken account of. I don't wanna say there's no, you know, reasonable version of that, and he makes an extensive case for it. But I can't go there, just because I don't have any evidence that there is any such thing. Sure. That I think is real good evidence. Anyway, another really persuasive one. Going back to Augustine, again, is that this sounds silly when you say it, but it's serious view. Evil doesn't really exist. Now, that seems offensive, almost. But Augustine is views and the St. Augustine view is that evil isn't a thing. It's not a, an entity or a substance, as philosophers like to say, it doesn't have any properties. It's a privation. And suddenly, it's an absence. The only things that exist are good. And he had an argument for this God is good. God couldn't produce anything that wasn't like God, or have a piece with God's, you know, Uzziah, or whatever. And so anything God makes is, by definition, good. And so if anything, seems bad, couldn't have come from God, and yet all things come from God. So where the hell could anything bad have come from? And his answer is, people choose to be less than they could. And in failing that way, and failing to live up to God's intentions for them. They create states of affairs that are less that are not optimal. They're less good than they could have been. But there's not a thing called evil. It's like when

Elliot 48:52

you turn off the lights exists left it's darkness. Exactly. Yes.

Randy 48:55

That's intriguing to me. Yeah,

Kyle 48:56

it's a nice metaphysics for you know, and this is like the standard view and like Roman Catholicism, for example. Evil isn't to the substance, it's not an existing thing. And so it kind of that plus freewill gets got off the hook, and does away with the problem of explaining where evil came from didn't come from anywhere, because it isn't real.

Randy 49:18

But we know evil is real. Yeah. Like we know they're evil people,

Elliot 49:23

because lights are actually dark suckers.

Kyle 49:29

Right this, you know, this runs into problems when you apply it to specific cases like most of these theodicy is due, it's very difficult to explain egregious, seemingly gratuitous pain, which is clearly a real thing by saying, Well, really evil doesn't exist. Yeah, but this pain in that case existed and it doesn't seem like there's a good reason for it didn't have to, for me

Randy 49:52

that that you feel like that's a little bit easier to get around. But when you see evil personified, is when I think it's harder to get around, you know, Hitler or Putin or you know, take your pick out all the low hanging fruit. When you see evil, and you see what a person can is capable of at their worst, then I feel like that theory goes out the window.

Kyle 50:17

Yeah, and even at its best, I still don't think it can account for why there's this much of that kind of thing. Sure, God could have done better, unless you want to take that live interview. And really, this is the best one, which I don't. There's another one called Soul building is usually the way it's phrased this goes back to a philosopher I really respect named John Hick. And he had this idea that similar to freewill in some ways, but a little bit different. God is interested in creating a kind of creature that God can be in relationship with what God really wants to do is create something like himself or herself.

Randy 50:52

So we're Eve, the soul is evolving towards God. Yes,

Kyle 50:55

evolution is a huge part of this view. In fact, hic went back to the beginning of Genesis and the garden story, and asked, is there really a fall in that and came away with the conclusion that there isn't, and that the Augustinian view, that's all fall there was mistaken. And that, in fact, you don't have something created fully good that then fell and needs to somehow get back to its original position, what you have instead is a, you know, millions of years history of God trying to build a creature, apparently, and that there's necessarily a lot of hardship and suffering involved in that kind of thing. And we're like, in the middle point, yeah, maybe not even close to the middle point of that process. This is his view. And God is building a soul. And that soul is ultimately going to look very much like God's self, which, you know, there's lots of theological precursors to this view. Interesting to

Elliot 51:49

me. Yeah, yeah, he's gonna go all the way to like creating a human, and then take millennia to figure out how to make it. Right.

Randy 51:58

But isn't that reflected in evolutionary law or theory, but

Kyle 52:04

yeah, and it has a lot of nice parenting analogies, though. Like, if I guess I'm just learning about being a parent, because my kid is too, but I want him to be a certain kind of person. And because of that, there's a limit on how much I can do, how much I can do for him, right. And there's a limit on how much help I can give 100%. And I have to set things up in such a way that there are boundaries, there's, there's so far it can go before I stop it. But there's got to be a lot of play in there. And so Hicks views that we're just we have a very limited perspective. And we're looking at this from, you know, evolutionary timescales. And we'd have no idea where this is headed. And you would expect there to be a lot of suffering that needs to be overcome as part of it. So that's been kind of persuasive to some people kind

Randy 52:50

of like that, because of what we know about. I was, I don't know what we know about it, but my understanding of the evolution of consciousness, right, going back to like cavemen and going all the way through in the tribalism and the all the isms, the misogyny, and the racism and the ethnocentrism, and all the wars that have been waged. And I would say that I'm not AI. But many have said that, like, human consciousness is evolving, and we're getting better. And we're getting, you know, like, I would say, we're moving more towards new creation. There's less war than there's ever been, there's less, you know, it's better to be a woman at any points in history than it is right now. It's better to be a person of color, or a minority than at any point in history, even though it's really, really terrible to be a minority in some Arab, some places. And it's really terrible to be an ethnic, you know, marginalized person. But the fact is, is that for all these marginalized people, groups, it's better to be alive right now than it was 100 years ago, and certainly 1000 years ago, and certainly 2000 years ago, you can go on and on. This has some, this has some flavor to me.

Kyle 54:01

Yeah, interestingly, one thing worth noting about that, and this is take us too far on a tangent, but that kind of point, which I totally resonate with, and I get, I've only heard it made by white dudes. Yeah, sure, including John Hick. Right. I've never heard of theodicy like this. And it probably are, you know, some that I'm just not familiar with. But these kinds of the Odysseys almost exclusively come from privileged thinkers. Now, you do have people like Martin Luther King, Jr, for example, who quotes I forget the theologians name, about the arc of history bends toward justice, you know, so there's obviously examples of it with

Elliot 54:35

empirical though Yeah, also data for exactly well,

Kyle 54:38

yes. But there there are, this is a huge debate. There's a person I won't name because I don't want people writing to me who wrote a book who's kind of known for this pushing this view. And yeah, he's very controversial because of it and especially controversial among minority thinkers and feminist thinkers for not taking seriously enough the the ways that the problems are still really pervasive and pernicious, which is and how they could just, you know, go back the other direction at any point if we don't keep trying?

Randy 55:06

Absolutely. And we're seeing that right now. But I would say, I would think historians would say there's that's a consistent movement, which is, you know, four steps forward, two steps back, and it's continuing, it's not a straight line.

Kyle 55:19

So maybe it's all headed somewhere good. This is like a teleological kind of thing. Like, it's, it's still that basic idea of there's a good greater than all the things we're experiencing, that will eventually be achieved, that will justify all of this,

Randy 55:32

and we can look back and say, We will be better than it was this that's maybe the most compelling thing. Yeah, to see if so,

Kyle 55:39

you know, people should absolutely read John hickeys worth reading and his his case for it is much more sophisticated than what I've delivered here. But I'm ultimately still unconvinced by it. I mean, it's, it's not the kind of thing that confronting, you know, it doesn't help me make sense of individual instances of suffering.

Randy 55:58

The two things that are compelling to me that it makes me want to look into it more, is the idea of the evolution of human consciousness, and also, the evolution of all things, you know, like, That, to me. Seems like two things running in parallel.

Kyle 56:15

Yes. So I'll say this much. I definitely think any successful theodicy or even reasonable theodicy has to take our actual nature into account as organisms into account. It has to be evolutionary in some sense. Yes. It can't just be, I don't know, your typical Sunday school kind of thing. We're, we're we were perfect. And then we weren't perfect, because there's some choices we made and all that we really need to get back to perfectionist to make better choices. I mean, it just doesn't take seriously our nature at all, or how we've evolved.

Elliot 56:44

Yeah. So as somebody who hasn't thought deeply about this, like, this is fun. Thank you. And also, I'm curious, maybe this is a dumb question. But like, are these mutually exclusive? No, we have because like atonement theory, like you kind of got to pick one.

Kyle 56:59

That's, I don't think you do. But that's, yeah, I get

Elliot 57:02

it. But there's like there's, there's things about them that are in contradiction to each other, some that are worse than others. Of course, yeah. This it feels like you could just kind of stack them all. And is there this kind of multiplicative effect, where you can start to weight them? Not on their own merits, but as it's like, yes, and yes. And then this, and then there's pretty soon there's a dumptruck.

Kyle 57:24

Right, yes, yes. And that's how, you know, theistic philosophers like to use arguments for God's existence, too, because each one is only so strong on its own. But if you look at like 12 of them, and they're each independently interesting, and calling attention to certain kinds of evidence that seem to have some weight on their own, put them all together, you might have a pretty good case, right? Something similar is true here. You could totally think freewill is a part of the story. You could totally think soul building as a part of the story, you can totally think eschatology is part of the story. Like, eventually, we'll be so far removed from our suffering and just perpetual bliss that it will seem, it'd be just be less important. That's another one I've heard. Another one that goes right along with that is fits nicely with this whole building thing is, I don't know what to call it. But they talk a lot about natural laws, and how just having, you know, physical laws working the way that they do entails a lot of suffering, but also a lot of beauty that wouldn't be possible without the suffering. So for example, think about a mountain range. And all of the things that had to happen tectonically for something like that to exist. Anything really beautiful in nature, has a lot of suffering behind, or at least the possibility for great suffering, right? I mean, earthquakes are an obvious example, there was just a major one that killed 1000s of people. Life music usually comes from death. Exactly. And yet without earthquakes, you don't have mountain ranges. And so that's another part of it that goes along. If God is trying to build a certain thing, maybe there are processes that are involved, that entail great suffering on the way. But then you still have to ask yourselves, why keep coming back to like, is that the only way God could have done it? Why wasn't there an option for an omnipotent being to have a process that achieved the same outcome?

Elliot 59:08

Is there a substitute for redemption though?

Kyle 59:10

What do you mean? Well, it's

Elliot 59:11

something like you said earlier, art, like it's the contrast that makes it beautiful. If if what we're headed for is redemption, if there's this beauty, if there's a restoration that happens if if somehow all of these things are made, right? It's only the extent to which they were wrong. You know, that that that creates the contrast. And if God is the one that then redeems all things, if it was just this kind of like incremental, like Yeah, he made it great in the first place, and then like, and now it's marginally better. Like that's, that's not. That's not as great as the story that I like anticipating and hoping to be a part of,

Kyle 59:51

yeah, the payoff has to be unimaginable. Yeah. Given the depth of the suffering. It can't just Be Martin, as you put it marginally better, it has to be something we haven't conceived.

Elliot 1:00:04

It's the depth of the suffering that makes that payoff. Right, is it not?

Kyle 1:00:07

It has to be at least that's how it works in art, right? When When you watch a great show, or listen to a great symphony, or whatever it has to resolve in a certain way to really be satisfying. And we all know when it doesn't land, right? And has to justify everything that came before it. And so the power of the evidential problem of evil is that it is impossible to imagine a justification or a resolution that justifies all this. I think it's simple, I can't do it. Yeah, that's, that's part of the power of the view, you know, stacked up against some of the most brilliant thinkers to have thought about this, and, you know, brought up really, really interesting solutions are not solutions, but at least theories hads to some kind of satisfactory answer. For my money, none of them are sufficient and stringing them together and making an interesting hybrid. I think it's a worthwhile endeavor. And I'm glad people do it. But again, for my money, none of them quite do it.

Randy 1:01:05

Is it primarily because you are a materialist?

Kyle 1:01:09

I don't know. I don't think so. I'm sure it's probably related in a way that I haven't thought carefully enough about. But no, I think this problem stands, regardless of that. I don't think believing in an immaterial soul, for example, would help that much. Yeah, I

Randy 1:01:24

only asked you if if you hold that position, because you're a materialist, because you are very much focused on what is not. You know, when we talk about spiritual things, or when we talk about possible miracles, or when we talk about supernatural phenomena, you think it's best for us to be skeptical instantly, that should be our first and most foundational orientation to any supernatural activity is skepticism. Would you agree with that?

Kyle 1:01:49

I tend that direction that yeah, that's, that's fair. I don't want to say make a kind of normative claim about anybody's you know, but I don't wanna say it's unreasonable for anybody to believe in something like that. But yeah,

Randy 1:02:01

even though you would say you've experienced the supernatural in some ways.

Kyle 1:02:05

Ah, I think I've experienced God, which I guess by definition is, in some sense, supernatural. I don't think I've have good evidence for any miracle. Yeah.

Randy 1:02:14

So I think where we can leave it in this first part is, there's some really convincing reasons not to believe in God.

Kyle 1:02:21

Yeah. Yeah. And, and some, you know, really clever and thoughtful responses. And we haven't gone

Randy 1:02:28

through all of them, right, even more than clever and thoughtful. Yeah, they're,

Kyle 1:02:31

I think, serious. They're sophisticated. They're serious. There are people who have spent their whole lives developing them really brilliant and careful people who took suffering extremely seriously. Still people who specialize in that. And some of them we haven't even encountered yet. But I think we've probably reached a point where we should I said at the beginning, we're going to get as far as we get. So maybe we should make this a part two, and go into some more of those. Because there are some interesting takes on the problem of evil that I wouldn't even call a theodicy actually. But they are a response in a certain way. And I want to give them their due

Randy 1:03:02

date. So let's look forward to listeners. We'll just let you mull on this. We'll let you pray about it. And stay tuned for the end of the conversation about the Odyssey and the problem of evil.

Elliot 1:03:15

Also now above our pappy level of Patreon support is the discover the answer to evil level in which Kyle tells you

Randy 1:03:24

that's a 16. That's a six figure level

Elliot 1:03:27

Deponia buddy, I wish

Randy 1:03:41

thanks for listening to a pastor, philosopher walk into a bar. We hope you're enjoying these conversations. Help us continue to create compelling content and reach a wider audience by supporting us at patreon.com/a Pastor philosopher where you can get bonus content, extra perks and a general feeling of being a good person.

Kyle 1:03:57

Also, please rate and review the show and Apple Spotify or wherever you listen. These helped new people discover the show and we may even read your review in a future episode.

Randy 1:04:05

If anything we said pissed you off. Or if you just have a question you'd like us to answer send us an email at Pastor philosopher@gmail.com.

Kyle 1:04:13

Find us on social media at peopIe web podcast and find transcripts and links to all of our episodes at pastor philosopher dot plus brown.com See you

Randy 1:04:22

next time. Cheers